“It is not enough to be white at the table. It is not enough to be black at the table. It is not enough to be ‘just human’ at the table. Complexity must come with us - in fact it will invite itself to the feast whether we like it or not.”

- Michael W. Twitty, The Cooking Gene

“As I knelt on the cool hardwood floor in my home office, surrounded by books that span nearly two hundred years of black cooking, I realized my ancestors had left us a very special gift: a gift of freedom, culinary freedom…. We have earned the freedom to cook with creativity and joy.”

- Toni Tipton-Martin, Jubilee

I. Feeding the Ghosts

We rarely tune into “food media” expecting, or even wanting, to be moved.

Instead, we look to satisfy milder cravings, more temperate urges—a desire to be entertained, or perhaps comforted.

At least, that’s true for Sol and me. After we put our six-year-old to bed, we often turn to Youtube cooking channels or feel-good food competition shows to unwind. It’s the viewing equivalent of warm milk and Oreos, rather than a bracing tumbler of scotch, for a nightcap.

Watching the first episode of the Netflix food documentary High on the Hog with tears streaming down my face, I realized this show would be different. Over four episodes, through countless interviews with black chefs, preservationists, and historians on both sides of the Atlantic, High on the Hog thwarted viewer expectations of what ‘food television’ can be. It also challenged our preconceptions about the history of U.S. food culture, offering a compelling counter-narrative that put African influences and African Americans’ contributions at the very center of American cuisine.

There was something different, too, about Stephen Satterfield as host. Missing were the usual bravado, worldly ennui, ego. Even among less forceful personalities in the food-travel genre, one registers a palpable distance between host and subject, as if the former had been teleported or CGIed into the scene. The aura of “TV celebrity” inevitably intervenes, precludes closeness.

High on the Hog, in contrast, upturned the convention of food-TV host as dispassionate authority. In fact, the first episode ends with our host weeping, in a powerful moment of vulnerability and release.

Satterfield, an Atlanta-born food writer, media entrepreneur, and former sommelier, stands at the Cemetery of Slaves in Ouidah, Benin, on the western coast of Africa. It is a mass grave and a memorial to those who were taken by slavers from their homes but did not survive the barracoons to make the trans-Atlantic journey.

What begins as an interview with the culinary historian Jessica B. Harris, whose 2011 book gives the series its name, becomes something more intimate and introspective. Harris turns the tables and asks Satterfield about his experience visiting the memorial at Ouidah for the first time. Voice breaking, he responds,

Harris then leads a tearful Satterfield away from the site; she holds him in her arms while he sobs.

Satterfield is on a roots mission, on a quest for self-understanding and cultural understanding, and he brings himself wholly to that project. It’s a joy and a privilege to be along for the ride.

Listening to Satterfield speak with such immediacy about his enslaved West African ancestors brought to mind another raconteur who wove together the Black American past, present, and future. Who endeavored, through food, to “take a completely shattered vessel and piece it together,” as Michael W. Twitty describes the improbable African American project of tracing ancestry.

I’m referring to American culinary legend and southern food champion Miss Edna Lewis. A Southerner who lived in New York City for decades, Lewis rooted her wide-ranging experiments and explorations as a chef, writer, farmer, entrepreneur, and activist in a specific culinary and cultural home: Freetown, Virginia, an unincorporated community founded by her formerly enslaved ancestors. She famously immortalized, elegized, and revivified this community in her 1976 cookbook, The Taste of Country Cooking.

Above all, Lewis’s writing and cooking insisted on the relevance of nourishing the ancestors. On the vitality of ghosts.

II. “Paying Down the Debts of Pleasure”

Even though I’m an experienced home cook, capable of re-inventing sad fridge leftovers into a more-than-passable pasta sauce or frittata or stir-fry, I’ve always loved cooking from recipes. I love them not as a formula to follow but for a story to savor: recipes as autobiography. It’s not that cooking another person’s food suddenly or necessarily leads to a radical understanding of their life experiences, but, still: it can open the door to a more tangible, embodied connection.

Of course, breaking bread together is not a simple cure-all, as anyone who has suffered through a contentious holiday dinner can attest. Nor is food always innocent. When it comes to the story of American food, black culinary innovations are often entangled in painful ways with the realities of slavery and its aftermath—from the enslavement of specific West African peoples for their expertise in rice cultivation to the invention of mac-and-cheese, that iconic ‘all-American’ comfort dish popularized and perfected by Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved chef, the French-trained James Hemings.

John T. Edge, director of the Southern Foodways Alliance,* writes that

“Paying down the debts of pleasure” can mean many things, all made more urgent by the pandemic—from paying restaurant workers living wages to supporting black, indigenous, and immigrant restaurant owners and farmers.

It can also mean honoring the ghosts—that is, telling a more expansive story of our nation’s history through food.

Because the roots explored in High on the Hog, while uniquely African American, are also indelibly American. Twitty’s “shattered vessel” is also at the wounded heart of our collective American identity.

III. “Radical Pastoral”

I first encountered Edna Lewis in the January 2008 issue of Gourmet magazine. It centered around southern food, and at its core was the posthumous essay “What Is Southern?,” published two years after Lewis’s death.

As a white New Yorker who had moved to Texas for graduate school, I had no previous ties with, and (at least initially) no interest in, the place I’d landed. Lewis’s essay was the first to stir a curiosity in me about living and cooking in the American South.

Full of rhythmic cadences, Lewis’s prose sings the past alive:

…

Lewis was born into the small black farming community of Freetown, Virginia in 1916. As a teenager, she joined the Great Migration north. She first rose to culinary prominence in the late 1940s, as co-owner and head chef of Café Nicholson, a bohemian, celebrity-filled spot in New York’s East 50s.

It wasn’t until the 1970s, however, that Lewis found her voice in print. First, in 1972 with The Edna Lewis Cookbook, a lively, improvisational affair that riffed on recipes from back home but also from Lewis’s experiences, travels, and imagination. Poet and cookbook author Caroline Randall Williams celebrates this eponymous volume as “a book with pretensions, and…a book with roots. It is glamorous and fabulous,” not unlike Lewis herself, poised, elegant, and self-secure.

The ever-elegant Lewis, with trademark chignon, on the cover of her first cookbook.

It’s her second cookbook, The Taste of Country Cooking, that has (perhaps too narrowly?) defined Lewis to many who are familiar with her work today. In Country Cooking, Lewis advocated for a seasonal, vegetable-forward cooking that long predates farm-to-table’s entry into the popular vernacular.

In Country Cooking, Lewis conjures up a community. She insists that food must be understood in context, and goes on to capture the beating heart of the people who produced the food, the relationships and rituals that gave it meaning. Her celebratory portraits of Freetown, Virginia remind me of the writer Zora Neale Hurston’s depictions of Eatonville, Florida, also penned from the exile of New York City.

But Lewis was constantly reinventing herself, and constantly hustling: she had been a talented dress maker, owned a New Jersey pheasant farm with her husband, and headed kitchens from Charleston to Brooklyn into her late seventies. As her friend, the southern-food personality Nathalie Dupree bemoans in a rather dishy interview, Lewis was not done right by the publishing industry. The Taste of Country Cooking defined an era and influenced generations of American chefs and home cooks, but it did not make Lewis much money.

Lewis spent most of her life outside of the South, and outside of Virginia (she passed her later years in Decatur, Georgia). As a result, Lewis’s food was both deeply rooted and open to improvisation and play. One could argue that this very grounded-ness was what gave wing to her experimentation.

As the cookbook editor and podcast host Francis Lam notes, Lewis was capable of a fierceness belied by the “nice old lady portraits” of her, subtly political acts in her storytelling about Freetown—Country Cooking was published, not insignificantly, in 1976, the nation’s bicentennial. For instance, Lewis deliberately omits Thanksgiving or Independence Day menus, while menus for Emancipation Day and Revival Week, two important African American celebrations, figure prominently.

Above all, Country Cooking is not a narrative of struggle. Even though the book acknowledges the reality of slavery** and the hard work of farming, it is animated by pleasure. What Lewis puts forth is both an alternative history and a blueprint for future generations. She tells the story of how one community of black Americans achieved la dolce vita, the good life. Their manner of doing so subverts today’s imperative to accumulate monetary wealth, to place nuclear family above created community. Instead, they put intergenerational care and responsibility at the center of what it means to live well.***

Here’s the recipe:

…

A central thesis of The Taste of Country Cooking—along with “What Is Southern?”—is that creativity is not something rarefied, exclusive. Creative acts can emerge out of physical labor, out of doing-for-others, out of what the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles calls “maintenance work.” It’s a thesis I’ve been exploring as well on this site about caregiving: artists do not need to lock themselves in a garret, away from human relationships and the busyness of domestic tasks, to add beauty to this world.

At the same time, creativity in the kitchen is complicated when it comes to the story of black contributions to American cuisine. Cooking can also mean drudgery; it can mean subservience; it can mean trauma. Excavating this history means unearthing inventive cross-cultural fusions and empowering stories of black entrepreneurship, alongside layers of stereotypes around what black folks eat and a lack of ownership of intellectual property.

In some sense, I wonder if Lewis would take issue with all of the posthumous accolades and attention because they might mark her as singular, exceptional—even though she was, without a doubt, singular and exceptional.

Lewis had a broader agenda of legacy and remembrance than any lone-genius approach to her biography can fully satisfy. She had ambitions to write a sweeping history of black cooks and their centrality to southern cuisine.

Food scholar Toni Tipton-Martin—who has in fact written such a book—recalls an impassioned letter that Lewis penned in the middle of the night, in the middle of radiation therapy, encouraging Tipton-Martin to pursue the work of excavating a more comprehensive and varied narrative of black American cooking. Lewis was passionate about the fact that African American cooks had established “the only fully developed cuisine in the country” but that they never fully owned the cuisine because “we did not own ourselves.” She urged Tipton-Martin to take these accomplishments out of the shadows, to restore the voices of black cooks that had, if credited at all, been minstrelized in white-authored cookbooks of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

…

The phrase ‘feeding the ghosts’ popped into my head one day in relation to Edna Lewis, without my knowing exactly what it meant.****

Here’s a guess. So many cultures around the world include ritualized offerings of food—from Mexican ofrendas to Shinto altars—to nourish the ancestors. These gifts of food and drink serve many functions, from honoring the elders to keeping the links between generations active.

I see Lewis’s writing, and The Taste of Country Cooking in particular, as a kind of literary food offering to the dead. The cookbook pays tribute to the resilience and creativity and joy of Lewis’s ancestors, rooted to the land, to the community.

At the same time, like Walt Whitman’s poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” Country Cooking is an offering to generations in a far-distant future, no less loved for their remoteness in time and space.

As Tipton-Martin observes,

Country Cooking is not an exercise in rosy-eyed nostalgia for a vanished past, but what cookbook author Kevin West calls a “radical pastoral.” It not only recalls what was; it also envisions what might yet be:

I love that image of Lewis’s work as a sort of written seed bank, storing up ancestral wisdom for a post-apocalyptic future. Lewis books are not simply a static portrait of a time and place. They also become a medium, a go-between that links a troubled present—a present where we have lost touch, lost our way—to the resources and knowledge of the past, so that we can build anew.

Ghosts, in short, are not just for haunting. They can be active, even benevolent presences. They can be mirrors, tricksters, provocateurs—sowing the seeds of self-awareness and transformation.*****

Lewis with niece Nina Williams (later Williams-Mbengue) in Unionville, Virginia, 1971. At age 12, Nina would help usher THE TASTE OF COUNTRY COOKING into being by typing up her aunt’s handwritten draft. Lewis and her husband also lived with Nina and Lewis’s younger sister for a time in Brooklyn. Although Lewis didn’t have children, she participated in crucial caregiving and mentoring relationships throughout her life.

IV. Soufflé

It’s late summer, shading into fall. Late summer’s bounty overlaps with the glorious produce of fall. A transitional time that gets me excited to cook but always leaves me a bit melancholy at the transience of the seasons. Cooking no longer has that carefree, bare-feet-caressing-grass kind of casualness; there’s a yearning for complexity, nuance to match this autumnal mood.******

This season, this moment, feels like just the right time to make Edna Lewis’s cheese soufflé.

If soufflé seems like a curious choice to honor the doyenne of southern food, think again. Historian Megan Elias explains that “(Lewis’s) soufflés, learned in a Virginia kitchen, did not fit with popular conceptions of American food.” Yet, French techniques found their way into the Virginia kitchens of Lewis’s formerly enslaved ancestors. They did so because, during slavery, both enslaved and free domestic staff trained in European techniques, became expert at crafting lavish, inventive French-inspired dishes to serve at white planters’ tables.

Soufflé—which might read as a sort of bougie, aspirational dish—also acknowledges Lewis’s cosmopolitan and complex identity. By extension, it shows the cosmopolitan, multifaceted nature of African American food. Elias again:

Lewis commanded her readers to drop their preconceptions of what was and wasn’t black.

…

It’s Tuesday night—a school night, nothing special—and as my husband and son bicker during violin practice two rooms away, I question the wisdom of this soufflé-making endeavor. It seems like an inauspicious evening to be communing with ghosts.

Still, I take a breath and begin. I butter a springform pan to serve as an improvised soufflé dish, then place it on the stovetop to warm, as Lewis instructs. Grate sharp cheddar and gruyere into a bowl (only the good stuff, Lewis insists). Separate eggs. Whisk together melted butter and flour, gradually adding the warm milk. Off the heat, mix in the yolks, the grated cheese. Add salt, cayenne, and dry mustard to accentuate the cheddar’s tang. Whip the egg whites into soft peaks by hand (this gets tedious, so I call in Sol to help). Fold the whites into the sauce. Carefully place the pan, laden with its eggy offering, into the preheated oven. Pace nervously.

I peek into the oven just as the microwave timer goes off, and there it is—

The soufflé’s delicate, improbable, magical rise.

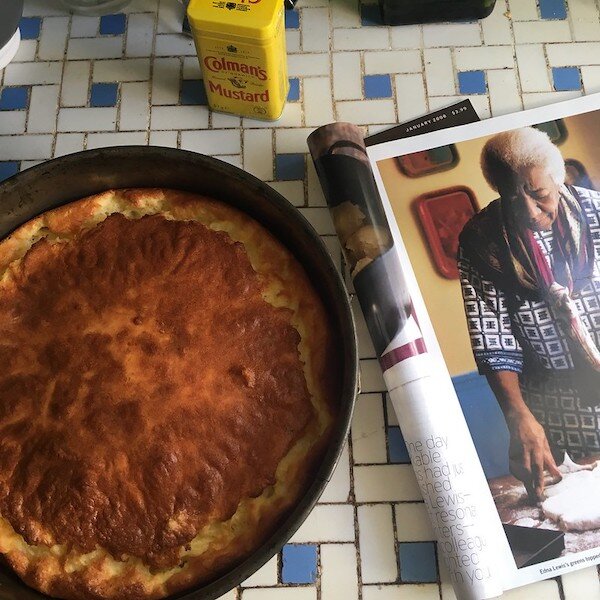

Lewis’s cheese souffle (already somewhat deflated) alongside a photo of her from my copy of the January 2008 GOURMET magazine that featured her iconic essay “What Is Southern?” (For the souffle recipe, head to Lewis’s 1988 cookbook IN PURSUIT OF FLAVOR or watch chef Sohla El-Waylly make it here.)

Postscript

As I began working on this post, some of our Austin-based family gathered to remember my father-in-law, a social worker and activist who died of cancer a year ago in Syracuse, NY. Our impromptu memorial centered around food, specifically the vegetarian food of South India that Peter so loved. Peter had spent a formative semester in India back in the early seventies; he also had family connections with the subcontinent.

One of his late-life delights was making idli, a savory fermented breakfast cake, in a special steamer that he purchased on a visit to Austin. I swear, he would bring that contraption and the fermented black-lentil-and-rice batter along to every family gathering and camping trip thereafter.

We assembled at Sol’s cousin’s place that night with our ad hoc offerings. Bhindi masala with fresh okra from our farm box. Paneer tikka masala, saucy and nutty and sweet. Pongal, a comforting rice and lentil dish enlivened with black peppercorns. Some naan and samosas ordered in from a nearby restaurant to round out the meal.

The vibe was chill and convivial. Once our bellies were full, though, we gradually transitioned to a deeper, subtler mood. We shared reminiscences, thumbed through photographs, while my son bounced from one lap to another.

As a former Catholic, I no longer believe in the literal bread-made-flesh, blood-into-wine of the Communion rite. But there’s no denying it: something profound, even spiritual, emerges when we eat together with purpose. I don’t mean to sell you on some naïve tale of harmony and understanding achieved at the table. (See Twitty above: “Complexity…will invite itself to the feast whether we like it or not.”)

I do believe, however, that the most humble, necessary acts of nourishing each other with food can help us access the tools we need to grieve, to connect, and to heal. Not a magic bullet, but a magic sauce, capable of reaching us where words and reason cannot.

Tear off a piece of naan. Scoop the spice-rich mixture into a warm pocket of bread. Let the stories and tears flow.

ACTIONS

If you’re here in Austin, Texas, we are in the middle of Black Food Week. I’m a little late to shouting this out (though there’s still nearly a week left of this three-week celebration!), but, of course, you can check out these Black-owned restaurants and food trucks any time of year.

Donate to The Edna Lewis Foundation, or visit the National Black Food & Justice Alliance for more on how to support Black farmers and growers.

NOTES

*Lewis co-founded a precursor to this organization: The Society for the Preservation and Revitalization of Southern Food.

**One of the most poignant and unexpected moments in Country Cooking comes in the book’s opening paragraphs. In spare prose, Lewis describes her enslaved grandmother’s traumatic experience of early motherhood. A skilled brick-mason, Lewis’s grandmother was forced to leave her children in their cribs for the full workday, unable to feed or tend to them until nighttime. Lewis continues,

Slavery is mentioned only briefly in the book, and Lewis is strategically silent about the larger Jim Crow realities outside the enclave of Freetown in the 1920s and ‘30s. Yet, this only-gestured-at context provides a necessary backdrop to the book’s emphasis on family and community, celebrated through food. When familial and communal relationships had been deliberately and cruelly disrupted for so many generations, food-based rituals that strengthen those intergenerational ties take on all the more urgency. Delight and joy around the table become acts of resistance, empowerment, and self-love.

***Caregiving, as well as the unexpected ways we make family, are through-lines in Lewis’s books and in her life story.

In Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original, her sister Ruth Lewis Smith recalls that, from a young age, Edna was charged with preparing breakfast and lunch for her six siblings. As mentioned above, her relationship with her niece was also a mutually nourishing one, and Lewis lived with Nina and her mother Naomi at the very time she was writing her most influential cookbook. I also learned from her obituary (though the details are hazy) that Lewis adopted a young adult from Africa, Dr. Afeworki Paulos.

Then, there’s Lewis’s late-life friendship with protégé Scott Peacock, whom she encouraged to explore his Alabama roots rather than seek for creative expression on the Continent. Known as “the odd couple of the South,” the black, octogenarian Lewis and the white, gay Peacock, nearly 50 years Lewis’s junior, co-authored a cookbook. As Lewis’s health declined, the two lived together in a Decatur apartment, and Peacock took on more of a caregiving role. (There’s some tension here, though, as Lewis’s family wished for Lewis to spend her last years with them in Virginia. I wasn’t able to unearth the full story.)

****Googling around later, I learned that this phrase is also the title of a 1997 novel by Fred D’Aguiar.

*****Only tangentially related: on the subjects of ghosts as transformative figures in our lives, check out Aoko Matsuda’s feminist retellings of Japanese ghost stories in Where the Wild Ladies Are. In the opening story, the protagonists’s bossy aunt, who regrets having committed suicide over a lover’s rejection, bursts into her niece’s apartment with a body-positive message. Soon, the protagonist is no longer obsessively getting her body hair removed to attract men; instead, she sees her hair as a source of power. Weird, but great!

******The pandemic has deepened this usual end-of-summer funk into a bona fide blues. Among other stressors, there’s a base-line thrum of anxiety about sending my first grader off to school each day in a mask and hoping for the best.