“I believed, even then, that we owe each other our bodies.”

- Eula Biss, On Immunity

I.

In 1948, Dr. Isabel Morgan published a solo paper that defied the scientific consensus on polio vaccination.

At the time, most researchers believed that a weakened live virus was the only path to a polio vaccine. Morgan, along with her team at Johns Hopkins, proved the viability of a killed-virus vaccine, which was more stable and easier to produce on a large scale.

Morgan had joined Hopkins four years earlier. She had previously done a six-year stint at the Rockefeller Institute, where she had earned considerably less than her male colleagues and had been passed over repeatedly for research awards.

Nonetheless, Isabel Morgan seemed poised to become a celebrity—with her doctorate in bacteriology from U Penn and family ties to scientific royalty (her father was Nobel-Prize winner Thomas Hunt Morgan). She took advantage of trite human-interest stories, like one that focused on her “upswept blond hair and sparkling blue eyes,” to advocate for women’s aptitude in the sciences.

Then, at the height of her career, within tantalizing reach of developing a viable polio vaccine, Morgan quit.

She married Joseph Mountain, a retired Air Force colonel, in 1949 and left Hopkins to become a stepmother to Mountain’s son Jimmy.

As one researcher put it, Morgan had “vanished into 1950s suburban domesticity.”

While immersing herself in the new roles of homemaker and stepmom, Morgan did continue her career in science. However, the Department of Laboratory Research in Westchester, NY was a far cry from the modern, well-equipped digs she had enjoyed at Hopkins.

Even more crucially, Morgan would never again work on polio, and no one at Hopkins would pick up the mantle of her vaccine research.

Polio historian David Oshinsky posits that Morgan was about a year or two ahead of Jonas Salk when she left the field. He speculates that, “Had she stayed the course, there’s a good chance today we’d be talking about the Morgan vaccine and not the Salk vaccine.”

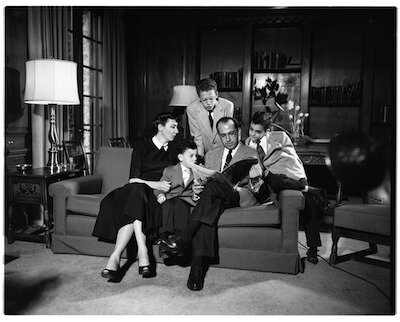

Images: Isabel Morgan in her Hopkins laboratory, late 1940s (at left). Jonas Salk (at right) pictured surrounded by his family in Ann Arbor, 1955.

…

It might be hard to imagine today, when polio has been nearly eradicated,** but polio was once “one of the most feared diseases” of the mid-20th century—made even more terrible by claiming children under ten as its primary victims.

In the U.S. alone, between the years 1950 and 1953 about 119,000 kids contracted paralytic polio, and over 6,000 died. For parents, summers—when polio outbreaks were at their peak—had a B-movie horror-flick vibe. Behind each trip to a community swimming pool or movie theater or potluck gathering lurked the possibility of contagion.***

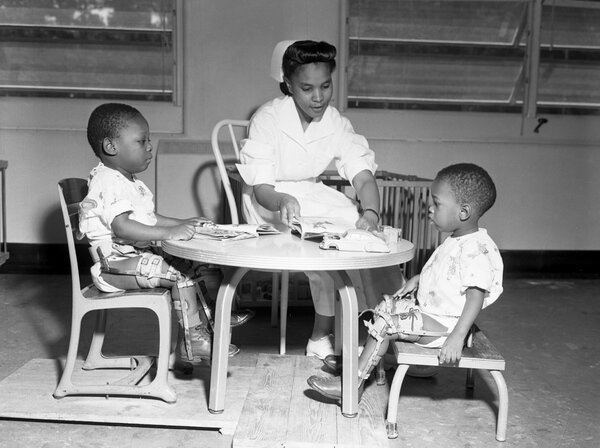

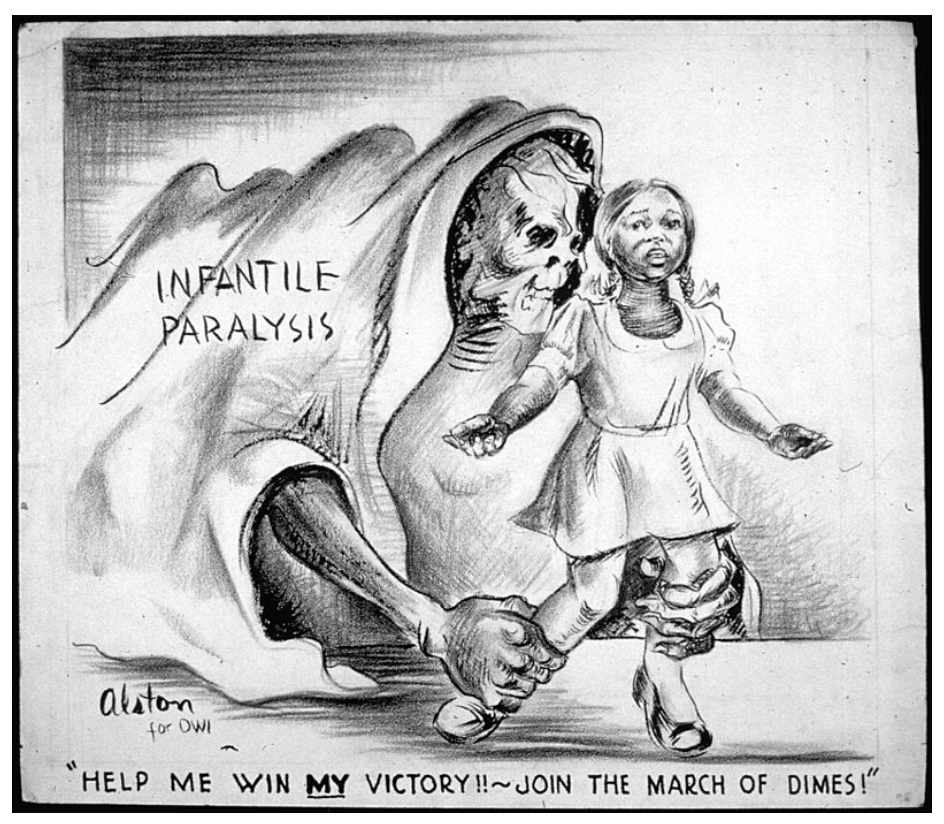

Images, from left: Nurse Grace Kyler working with polio patients in Tallahassee, 1953 (Via Florida Memory). PSA from The March of Dimes that tapped into parental fears around polio. Polio patients receive the news of FDR’s death at Shriner’s Hospital, PA, 1945 (Via Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

Given this context, did Isabel Morgan have a duty to kids and families worldwide to continue her research? Did absenting herself from the race for a vaccine lead to needless suffering?

And what did she owe herself? There’s a black box around Morgan’s motives in leaving the field of immunology. Reputedly, Morgan experienced an ethical quandary over taking the next step of testing the vaccine on human subjects. At age 38, she also felt called to become a wife and mother.

Many accounts deem Morgan’s choice of family life over vaccine research ‘unfortunate’: a loss of needed talent and expertise, as well as a loss of a potential role model to other women in the field.

But I’m hesitant to dismiss her choice of marriage and caregiving as somehow a lesser and/or an inexplicable one. As historian Anita Guerrini writes:

Elinor Bodian, a medical illustrator who was married to Morgan’s lab director at Hopkins, offered this gloss on her friend Isabel’s decision over half a century later:

I wonder, though, if Morgan’s era was actually “a different time.” In fact, her story intrigues me precisely because it crystalizes a host of timely questions about what we owe to each other and to ourselves when it comes to our creative pursuits.

What do we owe to our children, beyond the fundamentals of food, shelter, clothing, safety, love? What do we caregivers owe ourselves as human beings with a felt need to research, innovate, find self-expression? And how do we weigh the immediate demands of our domestic obligations against a more expansive sense of service to others?

Dale DeBakcsy’s profile of Morgan, questioning her decision to leave Hopkins and also raising concerns about animal testing in polio research.

II.

My husband laughs when I share the questions I’ve been contemplating for this post. They are, admittedly, comically large in scope. “Oh, so you’re tackling only the whole of moral philosophy!”

NBD.

Obviously, there are no ready answers to these thorny questions. Or rather, there are deeply personal answers, provisional answers. Answers that are accidents of economics and circumstance and temperament.

That doesn’t mean that they aren’t worth asking. In fact, these questions are ones that many parents have been grappling with over the past year or so of pandemic life, when our career responsibilities and caregiving duties have often clashed. Our responses to the questions of what we owe to our kids, to our communities, and to ourselves have, in the aggregate, been shaping the realities of many working families during the pandemic.

I’ve been thinking of Isabel Morgan when reading about the wave of women who have left science and tech careers in recent decades, largely to take on a caregiving role. Back in 2019, Nature reported that “more than 40% of women with full-time jobs in science leave the sector or go part time after having their first child.” Men, too, felt the impact of new fatherhood, albeit to a lesser extent: 23% of new dads cut back on hours or left the field entirely.

Sociologist Erin Cech explains,

The pandemic has only worsened these trends. Borrowing the language of infectious disease, The New York Times claims that COVID-19 has indirectly triggered an “epidemic of loss” of women early in their STEM careers. School and daycare closures exacerbated an already untenable situation, and the repercussions of this time will impact mothers’ careers and earnings long after the pandemic ends.

We might believe that we are working out individual answers in difficult conversations at the dining-room table or after the kids go to bed. And we are. But these more collective trends, unspooling across history, also challenge our illusion of agency.**** They suggest that, if we truly value the benefits of diverse perspectives in science, engineering, and tech, we are owed collective solutions.

III.

In the history of polio research, two names loom large: Jonas Salk, whose killed-virus vaccine was first administered in the mid-1950s, and Albert Sabin, whose oral live-virus vaccine, developed in the 1960s, is more widely used today.

But science so often works by accretion, collaboration. It is a collective endeavor that doesn’t fit neatly into narratives of individual triumphs or isolated ‘men of genius.’ And Morgan is by no means alone among the women—both professional scientists and concerned amateurs—to whom we are indebted for ending polio’s reign of terror in much of the world today.

These forgotten women include Dr. Dorothy Horstmann, whose research elucidated how polio progresses through the body, enabling the development of an oral vaccine. And Elise Ward, a cell culturist on Salk’s team who identified kidney tissues as the best medium for growing poliovirus—thus accelerating the pace of research. The list goes on.

More important than any single individual, however, were the “networks of women” whose names have been lost to the historical record:

Take, for instance, the female technicians at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, who produced the HeLa cells on which the Salk vaccine was tested. Or the mothers in Phoenix, Arizona who launched what would become the annual Mothers’ March, fundraising to support polio research in labs across the country, including Morgan’s and Salk’s.******

Delving into the past, minding the gaps in our popular accounts of polio, makes me think of this: we owe each other our stories.

A New York Times article from 1955, which includes a photo of four female technicians involved in the production of HeLa cells that would be used to test Salk’s polio vaccine. For more on the role of Black Americans in the polio effort, as well as the racist history around polio diagnosis and vaccination, see this article by Timothy Turner.

IV.

In 1960, Morgan’s stepson died in a mid-air plane collision over New York City. He was on his way home from college for winter break.

In the wake of that tragedy, Morgan shifted fields yet again. She returned to school, earning a master’s degree in biostatistics from Columbia, then taking a consulting job at Sloan-Kettering Cancer Institute.

As one colleague observed, Morgan seemed to shape her career “in response to blissful or sad events affecting her personal life.” There’s a curious thread between her work and biography: it was as if the joys and tragedies of her domestic life necessitated a research pivot as well. Whatever expectations were placed on her, Morgan seemed to know what she needed, and what she owed herself: a way of marking that she had been irrevocably changed, a pursuit of new research avenues to match the transformation within.

Dr. Morgan in January 1958, the lone female scientist among the honorees at the opening of the Polio Hall of Fame.

V.

Morgan’s life inspired me to write about the complex calculus of reckoning our debts: to our creative work, to our communities, and to our kids.

But it’s impossible to talk about Morgan’s field (immunology) without circling back to the epidemic du jour, and to the question of what we owe to each other in this historical moment.

In some sense, it has been the theme of this past year. The Black Lives Matter movement asks, in part, that we re-consider what we owe to each other. White people’s non-engagement, apathy, and silence around race and racial violence are not innocent; they are a way of actively perpetuating a harmful status quo. The climate movement asks us to consider how our short-term behaviors and disposable wants impact the lives and livelihoods of others. It also asks us to confront the environmental inheritance we owe to future generations.

And then, there’s the matter of vaccination.

Eula Biss’s 2014 bestseller On Immunity approaches the topic from a more personal, historical, and above all linguistic place. As a poet, Biss gravitates toward the language we use to talk about immunization, disease, and ‘wellness,’ and she connects that language to power and privilege. She finds that we draw sharp lines around ourselves and our families, that we view our bodies as disconnected from others’ even though herd immunity depends on the choices of the group, and upon a less individualistic way of understanding health.

According to Biss, immunity, “is a common trust as much as it is a private account. Those of us who draw on collective immunity owe our health to our neighbors.”

As I read about many of my fellow parents’ hesitation about vaccinating their kids against COVID-19, I want to channel Biss’s subtlety and empathy toward ‘anti-vaxxers.’ But I just can’t. Behind the language of personal choice and parental fretting, I also see an attitude of exceptionalism. It reminds me of Biss’s observation: we assume that public-health measures are “for people with less” and not “for people like me.”

Why is our ethos of care so limited, bounded by biological kinship? Why are we so keen on asserting our separation, on insisting that we are not intimately connected to everyone, and everything, around us?

I recall the Polio Pioneers, the nearly two million kids aged 6 to 9 who participated in Salk’s clinical trials of the polio vaccine, often referred to as “the greatest public health experiment in history.”

I remember Isabel Morgan, who gave herself whole-heartedly to her stepson Jimmy, forging a new and more expansive definition of family.

I think of the adults whose vaccinated bodies have been protecting my child’s unvaccinated one, enabling him to have more playdates and a bit of summer fun. He owes his health to others. One small way that he can repay that debt is by getting vaccinated when he’s able to. With the vaccine itself so politicized among adults, a robust vaccination program for kids is key to reaching herd immunity in the U.S., and to protecting us all from the evolution and spread of new, potent strains of the virus.

…

If I had to distill the concept of public health to its essence, it would be this single line from On Immunity: we owe each other our bodies.

From the moment we are born—in the moments we are being born—we are seeded with microbes from our mothers’ cervix, vagina, and vulva that defend us from disease while also overturning any notions of our ‘purity’ or our discreteness. Our inheritance at the very outset is one of shared immunity.

We do our best in modern family life—and in modern society—to keep ourselves separate as a means of keeping ‘safe,’ but here’s the truth: we can be each other’s contaminators, each other’s plagues.

And we can also choose to be each other’s shields.

Vaccine-trial participants, 1954. Via The March of Dimes.

NOTES

*With apologies to philosopher T.M. Scanlon and The Good Place.

**Polio is still endemic in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

***As the parent of an unvaccinated kid under 12 trying to navigate Summer 2021 in Texas, this scenario doesn’t really feel like such a stretch of the imagination.

****One of those patterns involves Morgan’s own mother Lilian. She, too, has been footnoted in history, which is why I am especially sorry to consign her to a footnote myself!

Lilian Vaughan Morgan was a bona fide biologist in her own right, if overshadowed by her Nobel-prize-winning husband (and former graduate advisor at Bryn Mawr) Thomas Hunt Morgan. Her research career was interrupted by the birth of her first child in 1906. During the 16 years she was raising their four children (of whom Isabel was the youngest), Lilian did not publish a single scientific paper.

According to a 1983 article by Katherine Keenan, Lilian’s return to the lab in her early 50s was a mixed bag: she was given a space to work at Columbia and later Cal Tech, her husband’s institutions, but did not receive an official appointment. Nor did Lilian collaborate with Thomas and his '“inner circle” of male graduate students. In the next three decades, Lilian Morgan would go on to publish twelve papers on the genetics of Drosophilia, but she never attended a scientific meeting or found her own professional circle.

Lilian Morgan, Isabel’s mother, in the lab (via Calisphere).

******Rita Algorri draws parallels between these crusading American mothers and their modern counterparts in Nigeria, where, as of August 2020, polio has been eradicated thanks largely to the efforts of young mothers engaged in community-led education and vaccination campaigns.