Time is not a river running inexorably to the sea, but the sea itself—its tides that appear and disappear, the fog that rises to become rain in a different river. All things that were will come again.” - Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

I.

If you have ever tried to shuttle a young child out of the door in the morning, you have witnessed an epic clash between two conflicting notions of time. You have confronted the flimsiness of the clock time that we use to order our days. The entire chronometric system foiled by a half-dressed toddler hunkered down in the entryway, eternally contemplating his elbow.*

Clock time is elusive to young children, in a way that’s sometimes humorous (“Mom, will I be a first grader in 70 years?”). But it’s mostly maddening when you have a bus to catch or a work deadline to meet.

Observing my son, I often wish I could dip back into the lazy, meandering stream of childhood time. I want to swim in that sense of immediacy. I long for endless summers, epic sessions of immersive play, and above all for that glorious feeling of boredom – time slowed to become almost perceptible, physical, as thick and still as the air on a muggy August day.

…

I had initially thought that this post on the architect Maya Lin would be about time in a different sense. Specifically, the span of a lifetime.

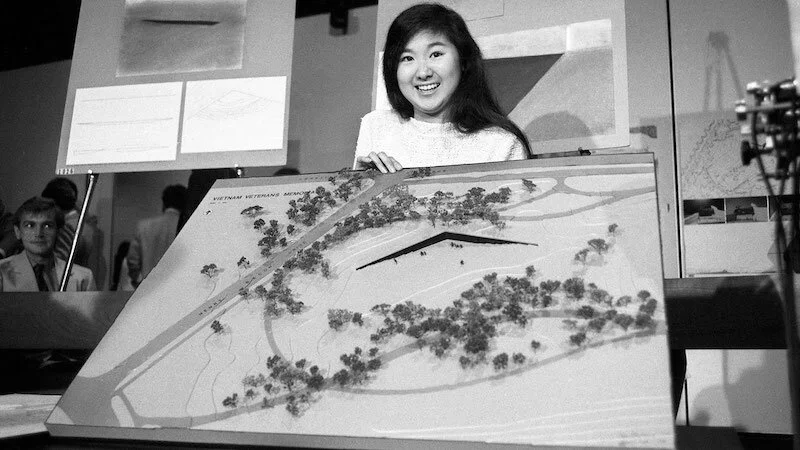

Lin was only 21-years-old, an undergraduate architecture student at Yale, when her design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was accepted. I was curious about what it would be like to achieve such early creative success, then have to figure out how to continue making meaningful work into later adulthood.

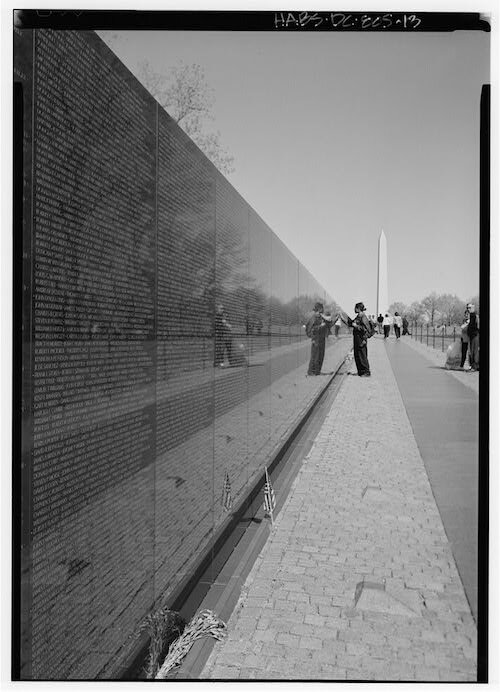

How did Lin keep producing? How did she avoid being crushed by the figurative weight of those two massive 246-foot-long slabs of polished black granite?

Lin holding a scale of the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial, circa 1981.

Instead, the time conceit quickly turned trippy. Lin’s work as an architect and an artist had me thinking about time – and space – on a far vaster scale. Yet it also helped, however briefly, to freeze time. To still the clocks (the biological clock, the career pressures) that distract us from our innate joy in the people we love, the work we do. That sever us from the natural rhythms that make the world go ‘round.

II.

You approach the burial site in Nikkō through a forest of Japanese-cedar trees. Wrapped in a living wall of towering greenery, you travel the narrow path, ascend the stone steps. You arrive at the spot where Ieyasu Tokugawa, the founder of the last Japanese shogunate, lies interred.

Down below, at the entrance, hunker Shinto shrines and out-buildings adorned in elaborate carvings and intricate gabled roofs. But that solemn tree-lined approach, and the relatively modest grave at the top, are what I’ll always remember from my visit to Nikkō.

The famed cathedrals of Europe are designed to shut out our contemplation of the natural world, to lift our gaze Heavenward. Similarly, monuments to secular leaders from the past often elevate our fragile human lives to objects of worship; they are idols dropped incongruously into the landscape, like the seeds of invasive species.

At the Tokugawa shrine, human ego seemed to fall away. Perhaps those stately cedars were trumpeting the beauty of Japan’s native flora, the specificity of its landscape. And in so doing, they cast some pale shadow of their glory onto the man who once united that vast realm. Regardless, it appeared, at least to this naïve visitor, like the trees were the ones giving Tokugawa legitimacy, conferring their ancient power. In the stillness of that magical place, the fleeting-ness of human time and the almost alien antiquity of tree time seemed to merge, be reconciled.

Goofy tourist picture of me and the majestic trees lining the ascent to the Tokugawa shrine, 2014.

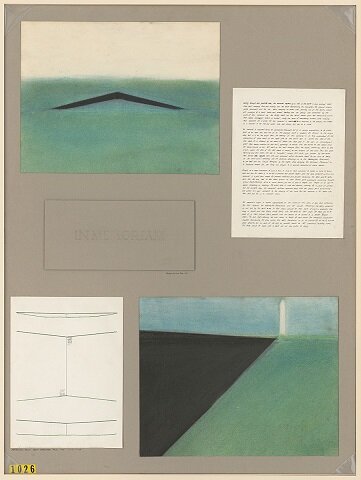

The American architect Maya Lin’s work also has this quality of bringing our attention to the land, and, by extension, of playing with our expectations about time. The memorial that made her famous, for example, offers visitors a seeming paradox. On the one hand, the memorial can represent rupture, the unnaturalness of young lives taken by war. Lin describes the initial inspiration for the memorial this way: “I imagined taking a knife and cutting into the earth, opening it up…”

Despite the violence of her imagery, she wanted to suggest that time, and the earth, would heal the initial pain, even if it left some scar tissue:

In this way, Lin was attempting to quiet the noise about time. This is a strange concept given the nature of a memorial: a remembrance of things past, of a particular moment in history—and, in the case of the Vietnam War, a particularly violent, contested history.

Lin, in fact, thinks of her work as an anti-memorial or anti-monument. Rather than elevating human history above the natural currents of time, she situates both our achievements and our struggles within an ecological framework. Like the Tokugawa shrine, the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial achieves a delicate balance: fostering intimacy—an emphasis on the personal, the human scale—through its catalogue of war dead, while also gesturing toward non-human time scales.

Images: Lin’s original design for the memorial (left); a visitor to the memorial in the 1980s, courtesy of the Library of Congress (right).

III.

Growing up in Athens, Ohio, in the 1960s and ‘70s, Lin knew little about her family history. Her parents had independently emigrated to the U.S. to escape the Communist regime. Their silences about the past extended to language. Her parents never spoke to her in Mandarin; she never learned their native tongue. And yet, in more subtle ways, their influences would permeate her art. Her father, an education administrator in China turned ceramicist in the U.S., crafted the clean-lined pottery the family ate off of, as well most of the mid-century furniture in their house.

It wasn’t, however, until Lin became a mother in the late 1990s that she had a breakthrough about the patterns in her body of work. Motivated by a new urgency to connect her daughters with their family’s past, she identified the previously submerged cultural expressions – the emphasis on simplicity, the value of harmonizing with nature – that had been operating below the surface all along.** She could now formalize them, use them more deliberately. Lin’s journey into parenthood had also become a journey of self-discovery.

Visiting her dad’s childhood home in Fukien, for instance, she experienced a jolt of recognition:

This architectural fusion of Japanese and Chinese sensibilities had the feeling of a homecoming. (However, she talks elsewhere of some ambivalence, given the historical tensions between the two nations, about identifying with the “wrong” East Asian culture.)

Just as new parenthood encouraged Lin to embrace a heritage that she had kept at arm’s length, it also meant confronting the more recent past. As a high school student in predominantly white, rural Ohio, Lin felt a pressure to assimilate: “all I wanted to do was fit in.” At Yale, she had even rebuffed an offer to join the Asian American Society; she describes herself as feeling “foreign” in that group.

Then there was the controversy over her design for the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial, which, among other reasons, was motivated by racism: that there was something unpatriotic about commemorating a war in Asia with a design created by an “Asian American.”

Like her famous memorial, motherhood offered the promise of healing, but the scar remained. Lin feared that her two daughters would never have access to a full sense of belonging to a culture, to a place. That, with a white Jewish father and a mom of Asian heritage, they’d be perceived as “half” rather than whole people.***

Maya Lin with daughters Rachel and India, and husband Daniel, circa the late 2000s.

IV.

Lin’s preoccupation with interweaving halves, with synthesis, takes on a variety of forms. Not only in her balancing of an American upbringing and an elusive Chinese past, but also in her attraction to both art and science. Lin recalls that as a child:

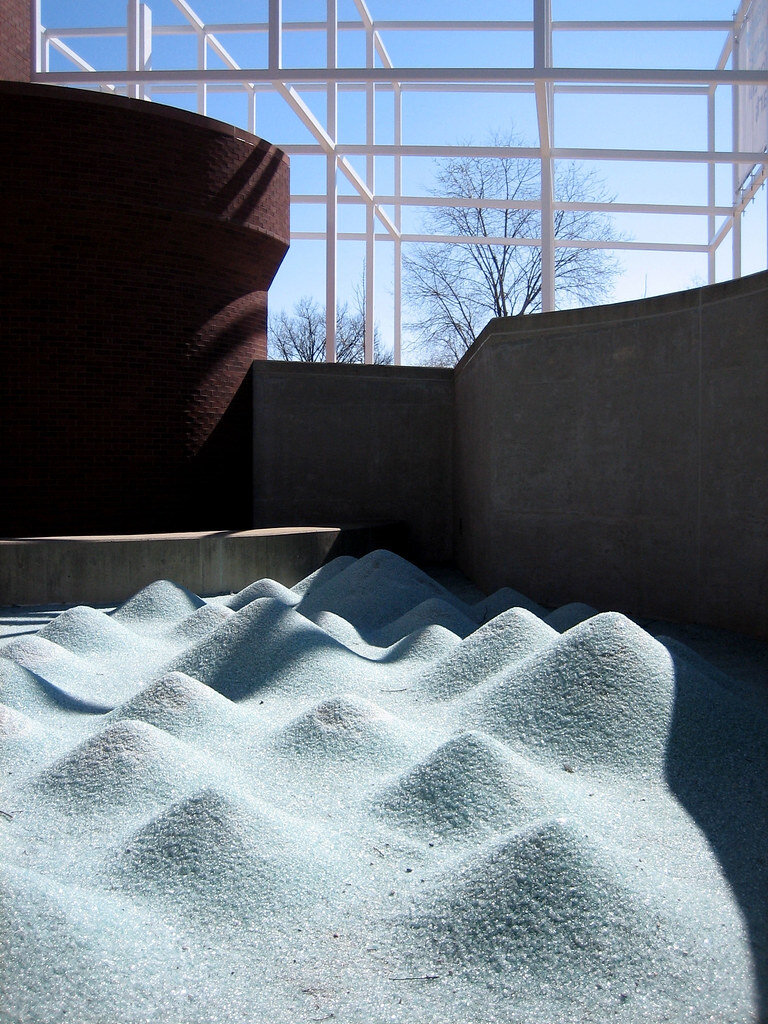

You can still see her reverence for nature in the way she designs structures that meld into the landscape or playfully bring the outdoors inside:

For all its attunement to age-old natural rhythms, Lin’s work has taken on a new exigence. Her formative experiences in nature have also fostered a sense of responsibility and a deep connection to environmental issues. In 2009, Lin designed an interactive digital project called “What is Missing?” The project maps human-caused extinction, as well as providing a dynamic, ever-evolving trove of information about and solutions to the climate crisis.

On the one hand, this work is a departure for Lin—disembodied, unrooted, activist. At the same time, “What is Missing?” is a variation on her lifelong theme of memorials. It charts species loss, habitat loss. It’s also rooted in her childhood explorations in nature, her sense of kinship with the non-human. And, in drawing together scientific data and design aesthetics, it weaves together Lin’s artistic and scientific selves.

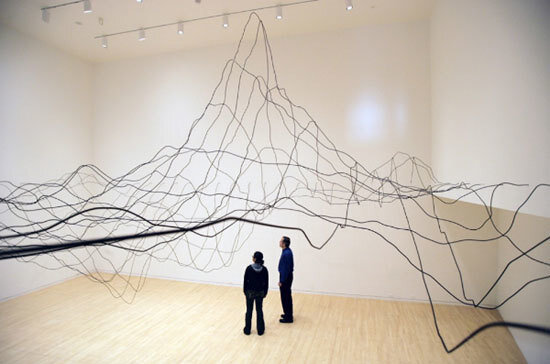

Images: A few of Maya Lin’s works, from left to right: Groundswell (1993), The Character of a Hill, Under Glass (2002), 11-Minute Line (2004), Water Line (2006), Storm King Wavefield (2007-8).

V.

There’s this gorgeous essay by Robin Wall Kimmerer set in a research forest in Oregon’s western Cascades Mountains. Kimmerer wanders for hours in a damp landscape of old-growth trees, attempting to bear “witness” to the rain. She begins to notice that the raindrops in a more nuanced and individuated way. As they interact with fir needles, rhododendron leaves, hemlock, cedar trees, moss … “the rhythm and the tempo (of the raindrops) change markedly from place to place,” and from plant to plant.

Rain might seem to be a single substance, but it turns out that interactions with tannins in the plants change the size of the drops, and hence the speed with which they fall:

A botanist by training, Kimmerer is attempting to integrate her scientific knowledge with indigenous understandings of the natural world. To do so, she must abandon some presuppositions, including the supremacy of human time. Or even the illusion that there is one single, reliable sort of time.

VI.

I turned 40 last month.

Intellectually, I can grasp that this milestone is a non-event, that it appears significant only because I’ve grown up in a culture with a base-10 number system.

But emotionally, that number looms. It feels like a reckoning. There’s an unkind voice in my head that says I ‘peaked’ a long time ago – maybe when I gave my salutatorian’s speech in high school, or was accepted to a fancy Ivy League college. Or rather, it’s more that I had this potential that never got actualized, that just dissipated. I began my hike up the mountain only to turn back at the first ranger station.

Now, in middle age, I am trying to start over. To pick up a creative thread that I’d lost track of somewhere in childhood. And, like the White Rabbit, I worry that I’m too late.

The problem with the concept of ‘peaking,’ of course, is that it assumes a particular way of viewing time: as an arc. This familiar chronology—the promising youth, the pinnacle of achievement in early middle age, the slow decline into elderhood—goes hand-in-hand with a reverence for Artistic Genius.

In Meander, Spiral, Explode, the novelist Jane Alison explores alternatives to the narrative arc that has come to define Western literature and literary criticism. She turns instead to natural forms – cells and networks, radials, fractals – to find the patterns that create a different sort of movement for readers.

Alison is writing about literature, of course. But I wonder if we can borrow her language for the stories we use to structure our lives. Maya Lin’s architecture, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s forest, the Tokugawa shrine…they all point toward different ways of ordering human experience.

What if Lin’s creative life can be understood not as an arc a but as a spiral, circling around these central questions of how to integrate East and West, art and science, human and non-human? Or as a fractal, in which each of Lin’s projects reiterates, in varying scales and forms, a version of her childhood love of nature?

Lin at work, 1980s.

As for me, I wish I could embrace the metaphor of cycles, seasons. Rather than dismissing these past four years of parenting as a setback to or a stalling out of my career, I might instead frame this time as a season of quiet preparation, latent growth. Whenever my inner critic shuts up for a moment, I can sense it. The roots are working busily underground, getting ready for the thaw.

VII.

Time feels mostly suffocating these days. It is as if I am being unceremoniously shoved along with a great, unrelenting press of bodies onto a Tokyo subway car at rush hour. Hurtling toward the future as I attempt to gather my wits, creative ambitions, and sippy cups about me. All the while being told by nostalgic older people to savor these moments with my young child, which “will be gone before you know it!”

Maybe that’s what draws me to Lin’s work. In the frenetic pace of modern life, what if we could find some measure of stillness? It could be a balm. An anchor.

There’s a paradoxical power in getting quiet, getting still. In looking around us to observe the different rhythms, time scales, that other beings inhabit.

If that longed-for boredom of childhood is no longer within our grasp, can we find other routes to being present (and staying sane)?

At least until that next morning rush out the door. When my kid will get captivated by a breakfast Cheerio that fell to the floor, go limp when I try to apply sunblock, dawdle interminably at the threshold…and remind me that we grownups are doing this “time” thing all wrong.

NOTES

*Speaking of contemplating time: I started drafting this post about two years ago, but somehow two years elapsed before I returned to it. I decided to leave the “toddler” bit as it was, even though my child is now 4.5 years old, because it fit in a way with the theme of this post.

**Lin recalls being told that the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial had a Taoist approach, but she knew nothing, had read nothing about this philosophy before designing the work: