“I did not want my tombstone to read, ‘She kept a really clean house.’ I think I’d like them to remember me by saying, ‘She opened government to everyone.’”

- Gov. Ann Richards

“I have a brain and a uterus, and I use both.”

- Rep. Patricia Schroeder, when asked how she could be both a congresswoman and a mother

Act One

Halfway through the first act of Ann, Holland Taylor’s one-woman show about the former Texas governor,* there’s a dramatic set change. The first scene has Richards addressing a crowd of graduating seniors at a college commencement turned trip down memory lane. Suddenly, the podium fades away, and a replica of the governor’s office lurches forward. Richards (played by the actor Libby Villari) enters the fray. She fields one phone call after the next as she paces around the room in sensible heels. And we, the audience, are thrust into the nearly-as-exhausting task of observing Richards/Villari excel at her job. In real-time.

This switch is where the play’s magic begins.

As I watched Richards go about the business of running a state—managing an inexperienced young staffer and a perfectionist speech writer, deliberating a 30-day reprieve from execution for a convicted murderer while crowds protest outside the Capitol, wrangling her four adult children to the family’s annual holiday shindig, all in the space of twenty minutes—one phrase came to mind: emotional work.

Yes, Richards was governor of Texas, but she was also “president of all the things.” I couldn’t escape the parallels between holding office and what comedian Biz Ellis describes as being “president”—i.e., the litany of organizational and managerial tasks that often fall on mothers.

Richards was keenly aware of these parallels, too. As she wrote in her memoir, “I learned more about management from running a household than I have from any other single occupation.”

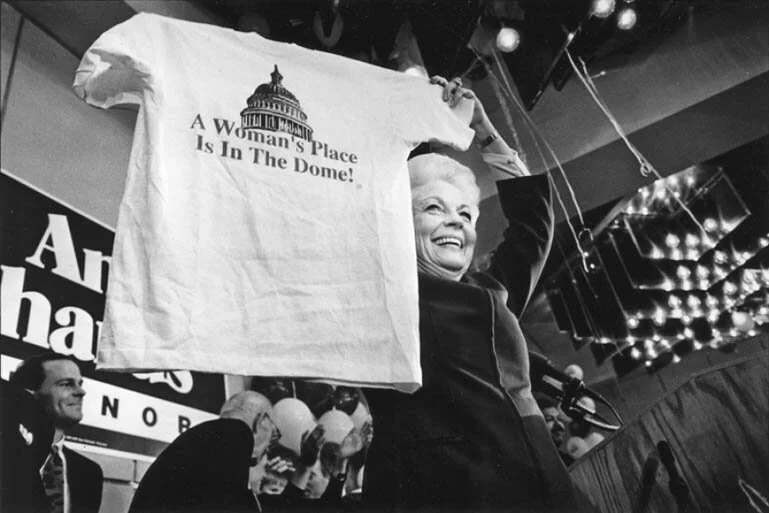

Holland Taylor in the original production of Ann.

The relentless demands, the frenetic pace, and the endless creativity in handling it all don’t let up until Richards’ capable assistant finally reminds Ann that she hasn’t used the restroom in several hours. (In a clever bit of writing, the governor’s fictive bathroom break also becomes the cue for the play’s actual intermission.)

I dare you to sit through Taylor’s loving, feisty, witty tribute and not fall madly in love with Ann Richards.

For those of us non-native transplants, it’s an unlikely seduction. (Ann’s long-time friend, the iconic Texan journalist Molly Ivins, famously quipped about Richards’ “Republican hair.” She might have lived in Austin for decades, but her look was all Dallas.)

Falling for Ann reminds me a bit of the way I was seduced by Texas itself.

To an outsider, those first encounters with Texas Pride can be puzzling. Why, you ask, as you glance around at the stunted mesquite trees and brave 100-degree days well into October,** is this state so damn infatuated with itself?

Then, you live here for a while, and something shifts. Texans’ brazen self-assurance can also be charming, like an ungainly cowboy who’s just sidled up to you at a honky-tonk to ask for a dance. The state’s ethos is big, brassy, and you start to think: maybe that confidence comes from someplace knowing, someplace true. Before you know it, you’re smitten.

That’s just what happened in 1988, when Ann Richards gave the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention. The play opens with a video clip of her electric performance that night, which instantly catapulted Richards onto the national stage. The speech has bequeathed us such gems as “Poor George [H.W. Bush]….He was born with a silver foot in his mouth” and “Ginger Rogers did everything that Fred Astaire did. She just did it backwards and in high heels.”

More than the words themselves, Richards’ delivery—her presence, her wit, her spark of connection with the audience—is what makes that speech so powerful to watch even today.

Richards’ story is vast and compelling in its own right, much like the state she once governed. According to my friend Allison, a Dallas native, Richards is the very definition of a “baller Texas woman.”

But tracing the arc of Richards’ journey into Texas politics expanded the scope of this essay even wider. I started getting curious about what had changed in the two-and-a-half decades since Richards left the Texas Governor’s Mansion.

Like so many mothers in politics, RichardS delayed her entrance into public service until her children were older. Where, I wondered, are the mothers who are actively raising children while on the campaign trail or serving in office? Have they begun to find a place in, and a pathway into, American politics?

And what might change—about the way we do family-leave policy or childcare in the U.S.—if we supported them, amplified their voices, so that they could become our voice in government?

Happy Election Day, y’all.

Second acts

Ann Richards was standing at the kitchen sink of her home in Austin’s Westlake neighborhood when her friends suggested she run for county commissioner. They had initially approached her husband, civil rights lawyer David Richards, about entering the Democratic primary. But, sensing his reluctance, they turned to Ann instead.

Up until that moment, in the spring of 1975, her relationship to politics had this near-and-far quality. Tantalizingly close but always just out of reach.

On the surface, Richards seemed to easily integrate raising kids with ongoing civic engagement. Her house served not just as a hub for a growing family of four children, but for intense political discussions with friends and a rotating cast of overnight visitors. Of those early Dallas gatherings, Mimi Swartz wrote, “Ann, pretty and sharp-tongued, became their star. She could cuss and laugh as loud as any man, and she could argue civil rights as well as she could make tamales.”

Richards had been sneaking a taste of the political life since the late 1950s, whether stuffing envelopes at NAACP headquarters, volunteering for the Kennedy/Johnson election campaign, joining the North Dallas Democratic Women, or supporting the United Farm Workers’ grape boycott.

In the early 1970s, she stepped up her involvement. She ran the young Roe v. Wade lawyer Sarah Weddington’s campaign for the Texas legislature, advocated nationally for the Equal Rights Amendment.

At the same time, Richards emphasizes that during those decades she was “a Mom” first and foremost. Her days mostly revolved around “birthday parties for little kids, Easter egg hunts, Indian Guide meetings, Campfire Girl meetings, Girl Scouts, ironing shirts, cooking large quantities of food not only for a good-sized family but also for parties and meetings.”

Mind you, Richards is not disparaging or apologetic about how she occupied her time. She pauses her memoir to point out the way that traditionally male forays into the public sphere get valued in a woman’s biography. In contrast, the daily caregiving and housework are glossed over, considered beneath the notice of the historical record.*** Richards admits to how tricky it is to capture the day-to-day contributions of caregivers, but she nonetheless resolves to dignify them with space in her life story.

Richards with her family in Austin, circa 1970.

Here’s how Richards describes her years as a housewife, using not one but two(!) endearingly down-home metaphors:

When she decided to run for office, Richards finally had to confront some long-held assumptions. She had been taught that women weren’t supposed to want things for themselves, whereas for over two decades she had been “running a household, catering the local Democratic Party, being everything to everybody…. There just was never a moment that I wasn’t doing something for someone.” Finally, she had to level with herself, admit that she was not running just to be a role model for her two daughters Cecile and Ellen. No, she was doing this for herself.

Her husband David was initially supportive. He encouraged her to run, told her she would always wonder about this chance if she didn’t take it. He vowed to become “the car pooler and the planner and the feeder,” taking up the domestic work she had done for the previous twenty-two years.

But right from the start, Ann sensed that this handing off of roles and responsibilities would do in her marriage. And it did. Ann and David finally divorced in 1984, after 30 years together.

In her own memoir, Cecile Richards, the former president of Planned Parenthood and Ann’s eldest daughter, details both her father’s progressive attitudes and his blind spots:

Intermission

At intermission, my husband’s aunt Sarah, who had joined me for the show, turns to me and whispers, “Can you imagine having Ann as your mother?”

It’s true that Richards comes across as…intense. During the play, she bluntly tells one staffer to “reconsider” her bangs. Cecile Richards recalls a department-store shopping trip with Ann before Cecile’s freshman year at Brown, during which, as usual, Ann commandeered “the wardrobe decisions.”

There was another side, though, to this bold, opinionated presence. Poised and unflappable in public, Richards privately relied on her kids, particularly after her marriage ended.**** Her son Dan, then 22, was enlisted during Richard’s bid for state treasurer, spending nine months on the campaign trail. Cecile left an organizing job she loved in LA, where she lived with husband Kirk and two-year-old daughter Lily, to campaign for her mother’s gubernatorial race.

Richards in her childhood bedroom with baby daughter Cecile, circa 1957. When Cecile was born, Richards briefly moved back into her parents’ house in Waco while her husband remained in Dallas. She found her lack of freedom as a new mother frustrating: “I had been running my own household for more than three years now, I was independent, and it was no picnic living in my parents’ house…. David was starting a new career [in Dallas] and I was in my old room.”

Humility, vulnerability…these are hardly the traits that first come to mind when channeling Ann Richards. And yet, she turned her divorce, her drinking—which unscrupulous political opponents used to attack her—into sources of strength. As governor, for instance, Richards continued to attend AA meetings. This was no faux populism, like eating the obligatory hot dog or pizza slice on the campaign trail. It was an act of frank and necessary honesty. Not only with the public, but also with herself.

…

Richards’ openness about her flaws, her failings, has found new life in more recent candidates’ bids for office. Her rejection of empty political posturing anticipated an emphasis on ‘realness’ that would characterize mothers’ campaigns in the 2018 mid-term elections, when a surge of women ran for office. Admittedly, Richards was not breastfeeding in her campaign videos, as at least two gubernatorial candidates (Krish Vignarajah and Kelda Roys) did in the 2018 race. But in their emphasis on unapologetically bringing their whole selves to the job, there are traces of Richards’ forthrightness and daring.

When it comes to male candidates, having a spouse and kids had historically telegraphed “wholesome and normal” (read: straight). For women, on the other hand, family has been viewed a liability. As political scholar Susan Carroll puts it, “Voters would look at a woman who was running for office with kids and say, ‘Well, how’s she going to Washington? Who’s going to be taking care of the kids?’” As a result, mothers have tended to start their political careers later, giving them less experience and time to network. And with rare exceptions, like the 1992 campaign of Washington State Senator Patty Murray (aka the “mom in tennis shoes”), mothers of kids under 16 have been told to downplay their identity as parents when running for office.

Illinois Senator Tammy Duckworth with her two kids. Photograph by Annie Liebovitz for Vogue.

Lately, though, mothers in politics have been setting precedents and otherwise challenging business as usual in government. Last year, after U.S. Army veteran Tammy Duckworth became the first senator to give birth while in office, babies younger than one were finally allowed onto the Senate floor during voting. Also in 2018, political hopeful and mother of two Liuba Grechen Shirley successfully petitioned the Federal Election Commission to use campaign funds to cover childcare expenses.

Candidates are now echoing Richards’ insistence that motherhood is a job qualification rather than an Achilles heel. On one of my favorite episodes of last season’s The Double Shift podcast, we meet Ashton Wheeler Clemmons, a mother of three and first-time political candidate campaigning for a seat in the North Carolina House of Representatives. Clemmons has young kids—a seven-year-old daughter and two four-year-old twin boys. She is running in part because she feels that “The voice of women who are actively mothering is not represented at our state legislature.” How, she argues, can politicians who raised their children thirty years ago understand the dramatic cost of daycare or the financial and emotional pressures on working parents?

Like Richards, Clemmons speaks about motherhood as training not only for the rigors of the job but for a more empathetic way of engaging in community:

Exit, stage right

After winning that initial race for country commissioner, Richards would go on to serve as State Treasurer in 1980s. She rightly bragged about the work she did in that office: “we will have made more money in eight years than all the previous treasurers—combined—in the 146-year history of the state of Texas. Not saved; made.”

Being good at her job, though, was never enough. In the essay “How Ann Richards Got to Be Governor of Texas,” Molly Ivins details how it took a string of incompetent good ole boys behaving with spectacular tone-deafness for Richards to have a fighting chance at the governor’s office. Like Republican opponent Clayton Williams, a wealthy oilman who joked about rape in front of an unsympathetic press.

In her four years as governor, Richards worked on prison and education reform while also striving to make state agencies more efficient and fiscally responsible. She appointed an unprecedented number of women and minorities to high-level posts, consistent with her abiding belief that Texas government should reflect the diverse population of the state.

In 1994, however, George W. Bush unseated Richards. Her ouster was part of the nation-wide Republican wave that also led to a conservative majority in both the House and Senate.***** Richards’ failure to secure a second term might also have stemmed from her decision, in gun-loving Texas, to oppose a concealed-carry bill.

When asked what she would have done differently had she known she would be only a one-term governor, Richards had this to say:

“I probably would have raised more hell.”

Breaking the glass ceiling + the fourth wall

Near the end of Ann, Richards/Villari exhorts audience members to run for office. Especially the women. She acknowledges our potential objections that there is something dirty, unseemly, corrupt about politics, then tells us to go out and serve anyway.

In this moment, Richards is ostensibly addressing a crowd of college graduates, as she did in the first scene of Act One. But the center no longer holds. Fact and fiction have blurred. Her straight-talk is aimed directly at us.

Today, the term “representation” is often used to refer to visibility, to seeing someone who looks like you in the workplace or in academia or on film. And, of course, these kinds of representation also matter: to the careers and identities and lives available to us as individuals, and to the health and richness of the society we want to cultivate. But, despite our distaste for or disillusionment with government, Ann reminds us that political representation can’t be discounted: “The simple fact of the matter is that politics and government involve all of us—as homemakers, as women with professions, as retirees, as students, as children—whether we choose it or not.”

Representation in government is key to meaningful change. It is the key.

If we don’t see ourselves in office, no one will. According to a 2017 study by the Barbara Lee Foundation, many voters are still unable to envision a space for mothers in politics. Voters questioned women’s ability “to balance the competing priorities of their families and their constituents,” especially when their kids were young.

Perhaps these perceptions (including self-perceptions) shifted irrevocably in 2018, when women began running, or preparing to run, in greater numbers. In 2014-2015, less than a thousand women contacted EMILY’S list with an interest in launching a political campaign; three years later, over 30,000 did.

For now, though, it’s unclear if these numbers were just a fluke, a temporary outpouring of civic energy and channeled rage in response to extraordinary circumstances.

I didn’t find any ready answers to my questions about mothers in office. Because we are still writing the script.

All the world’s a stage, darlin’

When the standing ovation came, it was unclear exactly who or what we were clapping for. Was it for the actor Libby Villari, who had hustled through two hours of a grueling performance? For the memory of Ann Richards, whose words and wit had animated the play from start to finish?

Or, was it for some mysterious third term: the vision of ethical, inspired public service that had been revived through that very interplay of biography and art, history and imagination?******

…

Sarah has a story for me as we exit the theater. Back in the mid-1990s, when she had first relocated to Austin from Delaware, she spotted Ann Richards on an airplane. Richards, who had recently left office, was sitting in first class. She wore a powder-blue suit and dark sunglasses.

“Hi, Governor,” Sarah ventured.

“Hi, darlin’,” Richards replied.

There was nothing remarkable about the exchange (if Richards forgot or didn’t know someone’s name, she would just “honey” or “darlin’” 'them). But what charisma she had…I could feel a bit of the charge of that moment in Sarah’s retelling 25 years later.

Now that this essay is nearly finished, I need to make a confession: I’ve never really been drawn to politics. The horse-race quality feels too akin to rooting for a sports team, another pursuit that mostly baffles me. As an English major who prefers literary nuance, I’ve rarely been moved by the bombastic rhetoric of campaign speeches. And as a card-carrying Gen X-er, I’ve hesitated to put my faith in a single individual, to idolize a fallible human being as some kind of political savior.

But Ann, and Ann, moved me. Both the play and the life that inspired it made me want to support the leadership of young mothers like Ashton Clemmons who are boldly entering the political arena. In part, since I know with absolute conviction—because I’ve done so myself, because I’m doing it right now—that we mothers have the capacity to lead.

In the audience that night, witnessing the glorious spectacle of a mother turned hell-raisin’ feminist and trailblazing Texas governor, I discovered a vestige of political optimism that I never even knew had been there in the first place.

ACTION

For more on how to support women and LGBTQ+ candidates, check out these six organizations.

NOTES

*As Richards quick to remind us in the play, she was not first female governor of Texas: that title belongs to Miriam “Ma” Ferguson, who was elected in 1924 following her husband “Pa” Ferguson’s impeachment. However, Ferguson openly spoke about her candidacy as a backhanded way for her husband to continue to govern. (She served a second non-consecutive term in 1932-34.)

**Not to mention the death-penalty rates, the poorly ranked public-school system, the state’s history of racial violence, and so on.

***I was also intrigued by what Richards had to say in her memoir about becoming a grandmother for the first time. She described it as another rite of passage, quite different from becoming a parent but transformative in its own right:

There’s something about a grandchild. It’s the first time you have the experience of seeing your life stretch out beyond you. You don’t really see it with your own children, because you’re so busy with the direct responsibility of their upbringing.

****Richards’ dedication to her memoir Straight from the Heart also supports this idea of her four kids as a stabilizing influence: “Cecile, Dan, Clark, and Ellen, my children, who, like the tail on a kite, have given me balance in the buffeting winds.”

*****In a 2004 interview, George the elder admitted to a sense of vindication when his son defeated Richards ten years prior:

When George beat her in his first run for governor, I must say I felt a certain sense of joy that he finally had kind of taken her down. I could go around saying, ‘We showed her what she could do with that silver foot, where she could stick that now!’”

******Playwright Holland Taylor intended Ann to blur these lines. As she explained to Amy Poehler: