“And, for your information, you Lorax, I’m figgering

On biggering

and BIGGERING

and BIGGERING

and BIGGERING….”

1. The question

About a year ago, I was having dinner in Manhattan with a good friend in her mid-40s. She had long ago decided not to have children. I have known this fact about her since we met over 15 years ago. It was as woven into the thread of her biography as her Midwestern-transplant’s desire to be “the nicest girl in New York City.” As predictable as our weekly Tuesday-night dates, circa 2005, to watch The Gilmore Girls after work in her Murray Hill apartment.

After our appetizers were cleared away, my friend popped the question. Were Sol and I planning to have more kids?

The question inspired, as it always does, a feeling of dread. Partly about the asker’s response. Will they nod politely, their expression full of silent, withheld judgement? More often, though, they’ll offer an unasked-for counterargument. (But what about a sibling to play with? When you’re old, your child will have to grieve you alone. Who would want that for their child? And so on.)

I also resent the social politeness that requires me to provide an answer when what I really want to say – channeling my inner five-year-old – is none of your beeswax. The question, so casual, so socially accepted, feels weirdly invasive. Like a non-medical professional asking, just out of curiosity, about your last bowel movement.

Still, I swallowed down those reactions. I answered that we hadn’t decided yet but were tending toward one child.

“I just can’t imagine not having a sibling!” she interjected, shaking her head. A thoughtful pause followed. “Can you?”*

My friend, who really is the nicest girl in New York City, was quick to reassure me that she wasn’t trying to weigh in on our decision. And I know that she’s weathered some difficult family history, which has made it so important in her own life to have a sister-ally a couple of years her senior.

But dang. Implicit in her remark was the notion that Sol and I had gotten the mathematics of ‘family’ all wrong. That the equation for procreation is 0 or greater than/equal to 2.**

How many times have all of us who are parents of one child had some version of this conversation, initiated by relatives, acquaintances, coworkers, cashiers? Strangers at the bus stop or on the street nodding toward my pregnant belly: “Your first?”

As if surely, inevitably, there would be more.

2. lonelyselfishmaladjusted

“Only.” This single 4-letter word condemns both the lonesome, spoiled, odd-ball offspring of a one-child home, and the parents (self-absorbed, smothering) who would create such a monster.

Demographers actually have a shorthand for the prevailing stereotype about only children, a run-together string of undesirable traits: lonelyselfishmaladjusted.

Veruca Salt, the ultimate manifestation of the only-child stereotype, from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1971).

As we’ll see, this stereotype is utterly at odds with decades of quantitative data. Across a variety of metrics, only children turn out to be routinely, boringly, just like kids with siblings. They differ, ever so slightly, on two measures: achievement motivation and self-esteem. Where they score higher than their sibling-ed peers.

So, where did the biases and baggage around only children originate? And why, even with robust evidence to the contrary, does the stereotype persist?

These aren’t idle questions. Despite the trappings of scholarly research, this post is something of a personal quest. Sol and I have been drifting, through our indecision, into the choice to remain parents of “an only.” I wanted to at least collect some data, weigh our options, rather than relinquish our agency to the vagaries of time.

A couple of caveats before we begin: in grappling with this decision for myself and for my family, I hope it’s clear that I am not passing judgment on the size of other families, large or small. How can I say what abundance might look like, feel like, for another person?

Let’s also acknowledge that choice in family planning can be, to varying degrees, a fiction. Just this year, twelve states implemented draconian rollbacks to abortion access (remember that a majority of women who seek out such services are already mothers). Then there are the wild cards of infertility, pregnancy loss, infant mortality. The steep price tag of in vitro, egg donors, adoption.

Even in less dramatic ways, I question the idea that we can plan some white-picket-fence future, where our reproductive choices are rewarded with healthy, thriving relationships among our children. Who knows what siblings will make of each other, what stories they will tell into adulthood? While many parents see having a second child as a ‘gift’ for their first, it is not always interpreted that way. We parents are not in charge of the script.***

3. “A disease in itself”

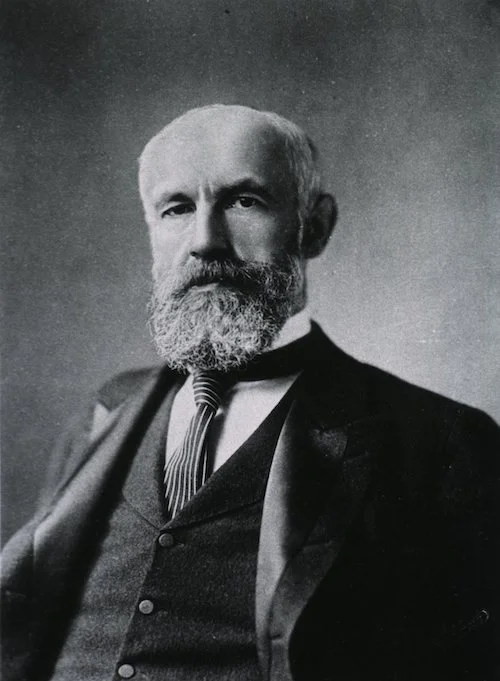

It turns out that the bias against only children has a very specific provenance, at least in the United States. It even boasts its own zealous crusader, in the person of American psychologist Granville Stanley Hall. In a 1907 lecture, Hall cautioned that “Being an only child is a disease in itself.”

Over a decade earlier, Hall had published a paper titled “Of Peculiar and Exceptional Children.” 850 out of the total 1045 cases examined were self-reported by a single teacher in the aptly named Normal, New Jersey. The study reflected a bias toward immigrants, with over half of “the non-American element…having disadvantageous traits.” The following year, Hall would revisit and add to the 46 cases of only children who had been deemed “peculiar.” His conclusion? They “tend to get along badly with others, not do well in school, and create imaginary companions.”

Granville Stanley Hall, the influential American psychologist who authored the only-child stereotype at the turn of the last century.

The sample sizes were laughable. The methods questionable. The implicit biases rampant. Yet, the lonelyselfishmaladjusted stereotype had, for the first time, entered the American imagination. As early as 1928, psychology studies were published that contradicted Hall’s findings. But the myth would not be easily unseated.

During the Great Depression, as Americans struggled to make ends meet, the number of single-child homes rose to 30%. In response, the press railed against this trend. Good Housekeeping, for instance, encouraged families of one child to muster some “pioneer courage” and add a second child, regardless of the financial hardship. Aside from fears about a declining population, xenophobia and racism were involved in these directives: an anxiety that immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe would outbreed the more favored Northern European stock.

4. Resource depletion

One contemporary psychologist who has made the study of only children her life’s work is UT Austin researcher Toni Falbo. She has conducted a meta-analysis of more than 500 studies over the past several decades, combing the data for 16 traits, from leadership to generosity, maturity to extraversion. The result, as mentioned above: single children score identically to kids with siblings, except for their slightly higher numbers on achievement motivation and self-esteem. (Psychologist Steven Mellor at Penn State has confirmed Falbo’s findings using independent techniques.)

Falbo’s own research, as well as a large number of studies in the meta-analysis, also suggests that only children are more cooperative than siblings and that they are better adjusted. According to Falbo, “Adjustment means the ability to deal effectively with problems that are both internal, like anxiety, and external, such as conflict with others.”

Demographers explain the slight advantage accorded to only children through the concept of resource depletion. With multiple children, parents have fewer resources – the obvious ones of time, energy, and money, but also patience, attention, even language – to distribute. Fewer books are read, fewer complex sentences spoken, as the household conversation, and overall tenor, defaults to the babyishness of the youngest child.

Now flip this phrase around, as journalist Lauren Sandler does in One and Only, and think about resource depletion from the parent’s perspective. Career, marriage, exercise, social life, volunteerism—these facets of a full self are already under siege with one young child, but suffer further with additional kids.

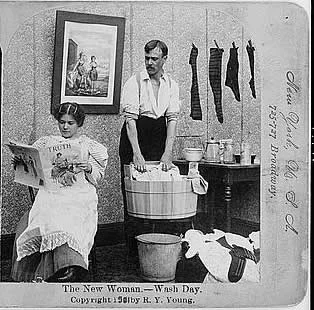

Remember our discussion of the Depression years, in which the U.S. saw a precipitous drop in family size? It turns out that economic factors did not solely explain this demographic shift. There had been a cultural shift as well. In the thirties, the U.S. was also coming off of the decades of the New Woman – a time of extended voting rights, greater workplace opportunities for women, and personal and sexual liberation in general. More and more women were opting for smaller families as a way to maintain their hard-won freedom.

‘The New Woman on Wash Day’ – R.Y. Young (The Library of Congress)

…

The New Women were onto something. In recent decades, demographers have shown that having one child tends to maximize parental well-being in a number of categories, from marital health to personal happiness:

Of course, these quantitative studies fail to capture the subjective nature of happiness when it comes to family size. They fail to consider accidents of temperament and circumstance. We do not experience life as averages or aggregates.

I also wonder how these metrics might change with the addition of universal childcare and robust social supports – if parents in the U.S. weren’t so stressed and isolated in the endeavor of raising kids, perhaps having multiple children would not pose such a challenge to maintaining a robust sense of self outside of those parenting and breadwinning roles.

5. Resource depletion (planetary edition)

The social pressure to have more than one kid reminds me of the more general tendency in the U.S. toward unchecked growth – the pervasive message to go after that bigger paycheck so you can buy a bigger house to hold more stuff. I’m not alone in noticing this link. In One and Only, Sandler looks at how our resource depletion as parents might also deplete the planet:

The daily grind of working and consuming leads to a kind of myopia. We become isolated from each other and from the larger threats to our collective survival.

Bill McKibben, a long-time environmental writer and activist who co-founded the climate-change non-profit 350.org, ponders the family-size question from an environmental angle in his book Maybe One. Written in the late 1990s, when McKibben’s daughter Sophie was four, Maybe One arrives at the unpopular conclusion that human beings, particularly in developed countries, need to stop proliferating. (McKibben practices what he preaches: he describes his vasectomy in amusing detail toward the book’s end.)

McKibben with his daughter in the late 1990s.

Maybe One raises the specter of rampant population growth as a reason for more of us to opt for single-child families. It’s not just that overpopulation in particular areas of the globe is taxing water resources, depleting soil, or diminishing air quality (although all of that is happening, too!). It’s that, through increases in carbon dioxide, methane, and other gases that effectively trap the sun’s rays in our atmosphere, the human population of developed nations is stressing – and warming – our planet in general.

Consider these numbers:

So, not all family-planning decisions are equal. In the U.S., our decision to keep ‘biggering’ our families will have an outsized impact on the future climate of the planet. Cruelly, those who are least responsible for climate change, those babies of the developing world, will suffer earliest and most severely from its effects.

Fewer babies would benefit the planet in a secondary way. McKibben suggests that being less depleted as parents would enable us to take action on climate:

In other words, having a smaller family doesn’t just create space for the personal fulfillment of adults. It also empowers parents to actively engage in civic life. To step away from the immediate demands on our time and energy and instead have a minute to envision – and then set about trying to create – the world we want the next generations to inhabit. To think big. To think ahead.

McKibben, like yours truly, is nervous about treading into these population waters. He doesn’t at all condone policy, like China’s,**** to limit family size. But he’s right to at least open up the conversation, to invite us to consider how population size affects climate. McKibben asks us to imagine an alternative, where we humans take up less space. At least right now. At least in what he refers to as this “special time,” the next 10 or 20 years that will likely decide the fate of humanity, and millions of species along with us.

Nina Paley’s brilliant (and biting!) short film “The Stork” (2002), in which, as she describes it, “a serene natural landscape is bombed by bundles of joy.”

…

The problem, though, is that this Should I…? question is often drowned out by the voice of yearning that responds. Decisions about family size touch on deeper currents of personal and family history, evolved urges and private desire. They’re matters of the heart.

If that biological craving for a second child were present, the kind I experienced when deciding to become a parent in the first place, would I be able to stoically resist it? Would my many rational objections (financial, practical, ecological) override such procreative instincts, honed over millennia of evolution?

Then again: earlier this year, mother of two Alyson Morgan posted on Maia Terra about how her environmental commitments won out over her longing for a third child:

It was Morgan’s frank exploration of both her personal ambivalence and her larger obligations that inspired me to write this post. To take a choice that I’ve felt fiercely protective of, that I’ve wished to keep private, and open it up – not to others’ scrutiny, but to my own more careful examination.

6. Be fruitful and…don’t multiply?

The naïve version of me who said to my partner five years ago, ‘Let’s try to make a baby,’ had only one motive in mind. Curiosity.

I wanted to know what it would be like, what it would feel like, to exist in relation to a child as their parent. And, in spite of my lifelong over-reliance on book-learning, I had a sense that this knowledge could only be gained, earned, through experience.

Curiosity is still at play in the vague notion of a second child. For all my complaints about parenting, I love being a mother, and I wonder what it would be like to do this job again, with a different human. What surprises, what delights and heartbreaks, would this new life bring into our home? Who would my first child become in relation to a younger sibling? And (this is admittedly a bit masochistic) how might juggling two kids challenge me, break me down, into a stronger version of myself?

…

At a recent 4-year-old birthday party I attended, a chubby, observant 3-month-old seized my finger. She clenched it tightly in her tiny, powerful wrist. As her mom and I chatted, I stood there, gripped by this baby, for a good long while.

That moment settled it. I will never know with certainty whether our decision to have one child is ‘the right one.’ Wistfulness, regret, and occasional bouts of Baby Fever might just come with the territory.

But where my curiosity is pulling me these days is mostly…outside. Grounded in the loving nuclear family Sol and I have created, I’m finally poking my head out of doors, looking for other signs of life in the forest. Heading toward a notion of kinship that extends beyond genetic ties. Toward a path of responsibility for lives beyond those of my own species. And possibly, probably, away from a future in which I am the parent of two children.

So, here’s my story, and I’m sticking to it (for now):

Sometimes, for some of us, one is just right. Because one child—one energetic, exuberant, growing life in your home—is a gift. Not a stingy or a selfish gift, but a bountiful one. Despite everything that food marketers have been telling us all along, maybe you can stop at one, and feel blissfully, magically full.

NOTES

*I have a close relationship with my brother, who is 7 years my junior. According to some definitions, this age gap even qualifies me as an only child.

**She’s not alone in this view. Given a hypothetical choice between remaining childless and having an only child, undergraduates in one study preferred no child by a margin of 6 to 1!

***A few years back, the Death, Sex, and Money podcast devoted an episode to siblings. I was astounded by the sheer range of interpretations from both sibling-ed and only children about the consequences of those relationships for their adult lives and personalities. Even if the data shows otherwise, clearly birth order or (lack of) siblings play an important role in the narratives we tell about who we are and how we came to be a certain way. This is why, to me, the only-child stereotype, while admittedly mild compared to many other stereotypes, can nonetheless have a pernicious effect.

****China, by the way, is a rich source of data for demographers investigating only children, and I’m sorry I didn’t have more space here to delve into cross-cultural comparisons. A quick synopsis: there was plenty of lame media coverage on both sides of the Pacific about the “little emperors” who would result from this policy. But in one generation, the social norms and cultural attitudes about only children have shifted dramatically toward greater acceptance of only children. (Of course, I’m bracketing a lot of other disturbing issues, such as a rise in female infanticide and the restriction of civil liberties in policing reproduction in the first place!)