“Women of color in America have grown up within a symphony of anger at being silenced, at being unchosen, at knowing that when we survive, it is in spite of a world that takes for granted our lack of humanness, and which hates our very existence outside of its service. And I say symphony rather than cacophony because we have had to learn to orchestrate those furies so that they do not tear us apart.”

- Audre Lorde, “The Uses of Anger” (1981)

Orchestrating the Furies, 1947-1959

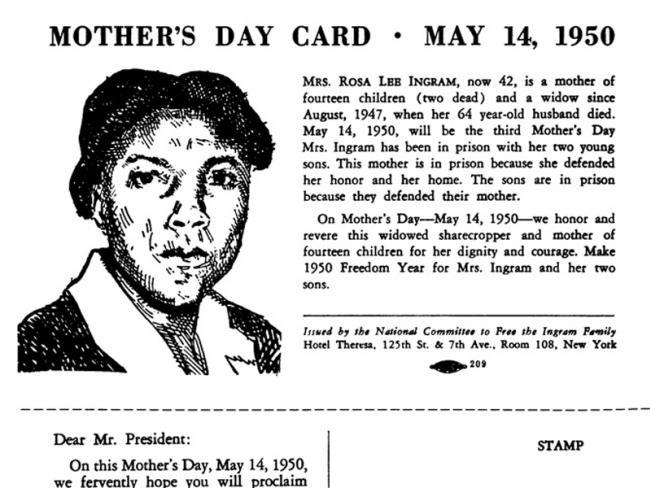

In May 1949, a torrent of Mother’s Day cards—10,000 of them—flooded President Truman’s office.

The cards arrived alongside a 25,000-signature petition demanding the pardon of Rosa Lee Ingram.* A Georgia sharecropper and mother of 12, Ingram had been convicted of murdering a white neighbor. He was a fellow sharecropper who had sexually harassed her on numerous occasions, and was attempting to rape Ingram when she and two of her teenaged sons acted in self-defense. Under pressure from groups like the NAACP and the Communist Party of America, Georgia officials had commuted their death sentence to life in prison. But the goal was to secure their release.

The greeting cards, and “the Mother’s Day crusades”** that had activists meeting with politicians, were the brainchild of the National Committee for the Defense of the Ingram Family. Formed in March 1949, the Ingram Committee was headed by communist organizer Maude White Katz and women’s club leader Mary Church Terrell, both veteran activists.

The campaign deployed the language of motherhood to argue for Ingram’s release. They described Ingram as “an innocent Negro mother…. [who] defended her honor, virtue, and home.” They framed Ingram’s human-rights case as “an outrage to all American motherhood and womanhood.”

Mother’s Day Card to free the Ingram Family. Via Wikimedia.

But these traditional terms belied the subversiveness of such claims. As historian Erik McDuffie observes, Ingram’s case made visible a host of interconnected oppressions faced by African American women:

Over the next several years, a number of organizations took up the Ingrams’ cause. (Despite the domestic outrage and international attention, the Ingrams still served 12 years in prison before being released.) One of the most progressive groups involved in their defense were the Sojourners for Truth and Justice, a left-leaning, internationally oriented cohort of powerful Black women leaders that included such luminaries as newspaper editor Charlotta Bass, tenants’ rights organizer Angie Dickinson, and anthropologist and writer Eslanda (“Essie”) Robeson.

Supporters of Rosa Lee Ingram wait outside during her 1953 parole hearing. Photograph by Norma Holt, from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, New York Public Library.

Long before Kimberlé Crenshaw developed the theory of ‘intersectionality,’ Trinidad-born activist Claudia Jones was writing of the “triple oppression” of classism, racism, and sexism. These Black female leaders also had a transnational lens; for example, in 1954, the Sojourners’ successor group took Ingram’s case to the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women, bypassing the U.S. government. They were articulating a new set of rules, outside the borders of race, class, gender, and nation.

…

When it comes to African American motherhood in the United States, the rules have never applied anyway. Demanding recognition as mothers, in a country in which slavery and mass incarceration have ripped apart biological families, has itself been a boldly countercultural act.

here’s the tricky part of the story: the culture of black mothering forged under such harsh economic and social realities is in many ways a robust and powerful alternative to the mainstream narrative of white motherhood and the apolitical nuclear family.

Media and politicians have historically tended to frame Black mothers as inferior, lacking, or otherwise “deviant”—from the forced separation of mothers from their children under slavery to the 1980s myth of the “welfare queen.” When, to the contrary, Black mothering in the U.S. is something to be both celebrated and emulated. It points the way forward.

As Parenting for Liberation activist Trina Greene Browne puts it: “We are raising children who were never meant to survive…People who are raising kids who were meant to survive have a lot to learn from us.”

“A Symphony of Anger,” First Movement (andante)

In Part One, we surveyed some of the ways that maternal anger has gotten political, from the anti-drunk-driving organization M.A.D.D. to the resistance tactics of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. Mobilizing politically as mothers clearly has had value and created a sense of empowerment for many women past and present.

At the end of the post, however, I explained why evoking my identity as a mother for political ends doesn’t fully appeal to me. I wanted instead to make common cause with other caregivers more broadly, locating the desire to create social change in an attitude, a stance of nurturing rather than a quality tied to my anatomy or gender. Even the word “Mother”—which for my husband evokes an image of a prim old-fashioned lady in a bonnet—just seemed to have too much cloying, sentimental baggage.

But reading about the history and practice of Black mothering* in the United States, its inherently communal and political orientations…well…changed my mind. I was casually expressing an ambivalence with the rhetoric around motherhood, when that very identity has been systematically denied to African American women in U.S. history. I had, in Trina Brown’s words, a lot to learn.

So, let’s start again. Da capo.

Second Movement (allargando)

The roots of a unique Black culture of mothering in the U.S. begin with a traumatic experience of uprootedness. Specifically, the profit-driven institution of slavery that systematically ignored, and often actively work to destroy, family configurations based in biological kinship. So, enslaved peoples adapted:

Out of this resourcefulness during slavery and the decades of segregation, violence, and incarceration that have followed it, emerged a parenting culture that differs in at least a few key ways from the dominant white culture. According to sociologist Dawn Dow, one such feature is the practice of “integrated mothering,” in which “child-care is a mother-centered but community-supported activity.”

Dani McClain, a journalist exploring the history and landscape of African American mothering at the start of her journey as a new mother, recalls how integrated mothering played out in her own Cincinnati childhood:

This tradition of what Patricia Hill Collins calls “other-mothering”—looking out not just for your kid, but for all kids of color in your community—contains the seeds of public service and political action. According to Collins, a community-oriented approach to defining family has often led Black women into civic engagement:

McClain also sees in this outward-looking orientation a more basic fight for survival:

In other words, questioning authority, fighting for social change comes with the territory. Because the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Two young boys at a camp in Dallas, Texas, circa late 1940s/early 1950s. Photograph by Marion Butts. Via the Texas African American Photography Archive. I decided to post this sweet image instead of its horrific inverse from the same time period: the open-casket photograph of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy who was brutally murdered in Mississippi in 1955. His mother Mabie Till-Mobley insisted on an open casket to mobilize civil-rights action: another example of a mother’s grief, and her rage, being channeled into social change.

Of course, it’s also important to acknowledge some of the trade-offs of this communal focus for individual women, including the burden of the ‘Strong Black Woman’ image. Collins again: “this work often extracts a high cost for large numbers of women, such as loss of individual autonomy or the subversion of individual growth for the benefit of the group.” To “live for the we,” as community organizer Cat Brooks tells her daughter they must, imparts a great sense of connection and purpose. But it is also heartbreaking. And exhausting as hell.

Third Movement (con anima)

Which brings us to anger. As the poet and activist Audre Lorde insists in her influential 1981 lecture “The Uses of Anger,” anger has value; it contains both “energy and information.” Lorde is writing in part about the anger between women, the silences, wrong assumptions, and indifference that have also characterized the history of gender when it intersects with race.

For instance: while the second-wave feminism of the 1960s and ‘70s made strides on workplace discrimination and reproductive rights that benefited all women, it also tended to dismiss Black women’s unique perspectives and concerns around work and motherhood.***

In Betty Friedan’s 1963 bestseller The Feminine Mystique, she diagnoses “the problem that has no name”—the ennui, dissatisfaction and depression that characterized the housewifely role for many middle-class white women after the Second World War. But what if you had been working outside the home that whole time, as women of color and working-class women had been doing?

Dow explains how the feminist analysis by “white motherhood society” didn’t really match Black mothers’ beliefs and self-image, including the idea that work and family are inherently at odds****:

At the same time, both feminism’s second wave and its turn-of-the-century precursor often ignored the issues at the forefront of Black mothers’ concerns: the economic instability and physical violence threatening their communities.

In the past few years, these words from another piece by Lorde have been rattling around in my head:

This reality, though, of the stark differences in our fears and challenges as mothers, can also lead us toward points of unity in our parenting approach. According to Dow, another facet of Black mothering culture in the U.S., and another way that it ‘gets political,’ is the widespread belief that conversations about race are an essential part of raising children. As Dow puts it, many Black mothers she studied felt that “considerations of race and racism should be consistently present in determining how to best raise children.” In contrast, white parents prefer to take a “color-blind” approach (i.e., avoiding conversations about race and racism) that is ultimately more damaging to social progress. We need to face up to our own discomfort, or fear of getting it wrong about race, and have those talks anyway: they are a part of our responsibility as parents and citizens.

…

Delving into this research on maternal rage and political action has underscored for me the richness and complexity of the story of motherhood. As Katherine Goldstein insists on The Double Shift podcast, that story is never “one note.”

This post is not intended as just some feel-good celebration of difference, though. As journalist Amy Westervelt observes, we can find concrete takeaways for rethinking the culture of parenting in the U.S. Aside from the importance of bringing anti-racist conversations into all homes, “integrated mothering” or “other mothering” provides a powerful model for raising children outside the mainstream narrative. Even if we don’t have relatives nearby or don’t belong to faith communities, what might we do to support fellow parents and their kids? How might we turn our focus outward, start caring for each other, watching out for each other beyond the limited confines of our nuclear-family boxes?

One last thing: as women it takes great skill not to suppress, or shake off, or laugh off our anger. (Or, classic white-lady move of which I have been guilty many a time, to substitute tears for what is actually fury.) Following Audre Lorde’s cue, I’m hopeful about the large-scale change that comes, both within us and in the world around us, when we transform our anger into energy and information we can use.

A howl can turn into a painting, or a protest, or a song. Our rage can become eloquent, artful.

Audre Lorde, 1983. Photograph by Robert Alexander.

Coda

This isn’t my composition, my “Symphony of Anger,” after all. I am merely an audience member, albeit one who has left the performance transformed.

So, to quote my childhood reading hero LeVar Burton, you don’t have to take my word for it:

Deesha Philyaw, “Ain’t I a Mommy?” – this article is a great way into the problem of the dearth of representations of Black motherhood.

Janet Stickmon, To Black Parents Visiting Earth: Raising Black Children in the 21st Century – a collection of letters reflecting on the absurd modern social climate around Blackness and the challenge of raising confident kids within it.

Dani McClain, We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood: I leaned pretty heavily on this book when researching this post… A great combination of small, carefully observed moments from her daughter’s first two years of life with broader insights about the past and present of Black mothering culture in the U.S.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs, China Martens, Mai’a Williams (Editors), Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines – Through a variety of styles, genres, and voices from women of color, this anthology addresses this question of how, and why, motherhood and civic engagement overlap. I first came across Rosa Lee Ingram’s story here.

Nefertiti Austin, Motherhood So White: A Memoir of Race, Gender, and Parenting in America - I haven’t read this one yet, but the latest interview with Austin, an adoptive Black single mother, on One Bad Mother podcast was delightful. The memoir discusses both the history and invisibility of adoption in the African American community, as well as stereotypes around single Black motherhood that she’s confronted as an adoptive parent.

NOTES

*The petition was also accompanied by a request to meet with the president. Truman initially accepted the invitation, then claimed he was “too busy.”

**In Part One, we talked about the ways that Mother’s Day’s original collectivist intentions in the 19th century got defanged in the early 20th. But note here how the women organizers of the National Committee for the Defense of the Ingram Family reinvest the holiday with political meaning, import.

***Not only were Black women’s concerns often written out of the social movements of the 1960s and ‘70s; their presence and leadership have been written out of history. The Code Switch podcast offers the fascinating story of “Freedom Rider” and feminist Mary Hamilton, whose example illustrates both the vital contributions of African American women and the ensuing process of erasure.

****Amy Westervelt does note a downside to this pro-work perspective: given the tradition of work outside the home, African American stay-at-home moms have faced some stigmatization within the Black community.