Asymmetry (general): lack of equality or equivalence between parts or aspects of something

Asymmetry (particle physics): the absence or violation of symmetry in the weak interactions of subatomic particles*

Last summer, I met a woman at a writers’ conference who belongs to a group that she and her friends call the $100K club. Savvy self-publishers, they harness micro-trends in bestselling genre fiction on Amazon to make a quick buck.

Her frankness about her financial ambitions – her ambition in general – startled me. Internally, I was quick to dismiss what I perceived as her crass commercialism. I was oblivious to the way that gender might have framed my snap judgment of this fellow writer and mother.

Awhile back, I completed a free e-course on publishing. In the course, writing coach Cathy Yardley asks writers to evaluate what’s motivating them to seek publication for their work: money, fame, or artistic expression?

My super-ego rushed to respond to the question: “Why, artistic expression, of course!”

But these drives are not so easy to disentangle. Yes, I am intrinsically motivated to write. Yes, I believe that my book offers a unique angle on Ada Lovelace.

None of this negates the fact that a part of me longs for my work to be noticed, admired, celebrated.

As my three year old puts it, with a striking self-awareness that I lack at 38: “I want your attention.”

I have been socialized to avoid verbalizing, or even thinking about, ambition. This taboo runs deep. Typing the sentence above, for example, I put my desire for acclaim into the mouth of my child. Deflecting, hedging, turning it into a version of ‘kids say the darndest things.’

In the recent essay collection Double Bind: Women on Ambition, editor Robin Romm observes a similar ambivalence around the word ambition, even among the book’s contributors. As for herself, she writes,

In my twenties, I inherited what so many young women inherit, the pervasive sense that striving and achieving had to be approached delicately or you risked the negative judgment of others.

Motherhood can be a powerful tool for mitigating, ‘softening,’ these expressions of ambition.

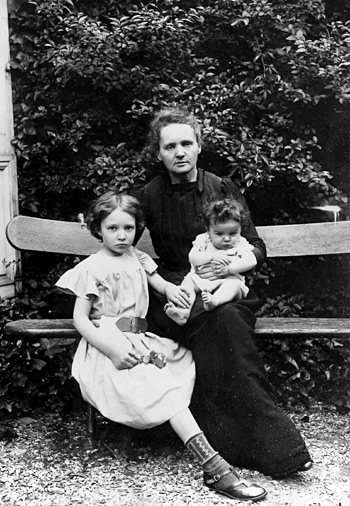

Images: Mary Cassatt, Emmie and her Child (1889). Marie Curie with daughters Irène and Ève (1905).

A recent essay on Lady Science documents the long history of women in science and medicine being cast – and often casting themselves – in terms of their maternal qualities. Emphasizing their femininity (here signaled by their roles and relationships in the private sphere) would make their trailblazing presence in the professions more socially palatable.

The author, Amanda Barnett, looks at the ways this language persists. Barnett points to a student-newspaper profile of the honors-college dean at her university - an accomplished neuroscientist who describes herself in the article as “a mom first.”

Although Barnett doesn’t spell it out, the label ‘mom’ reads as non-threatening. Identifying as a mother enables women to achieve professional success without rocking the boat of social norms. It conforms to gendered expectations of modesty and service even in leadership roles.

This picture of female ambition is further complicated when race and gender intersect.

Which brings us (at last) to Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu.

Hailed in the mid-twentieth-century as the “Queen of Physics” and the “Chinese Marie Curie,” Dr. Wu became an expert in nuclear fission and beta decay. Although she had a rich and varied career, Wu’s most significant contribution to physics was in overturning the law of conservation of parity, which had been deemed a fundamental law of physics. At the time, it was believed that laws of symmetry governed all aspects of nature, including subatomic particles. For six months in 1956 into 1957, Wu and her team worked tirelessly in New York and Washington to generate experimental proof that parity was not conserved in weak interactions.

The research was so groundbreaking that the Nobel committee awarded a prize at record speed – that very same year. In a controversial move that speaks both to a bias against experimental physics and a bias against women, the Nobel went to two male theoretical physicists. Wu’s could have easily been the third name.

Chien-Shiung Wu at the lab (via Library of Congress).

In the decade prior, Wu also contributed in multiple ways to the Manhattan Project, the U.S. research and development program that produced the first nuclear weapons.**

Hearing that Wu was an elegant and resourceful experiment designer, famed atomic physicist Enrico Fermi consulted Wu when attempting to produce the first large-scale, self-sustaining plutonium chain reaction. She successfully trouble-shot his experiment design.

At Columbia*** in 1944, she also worked on purifying uranium for use in the atomic bomb. Because she was not based at Los Alamos, Wu, along with her physics colleagues at Columbia like Maria Goeppert Mayer and Jane Hamilton Hall, were deemed ‘peripheral’ to the Project.

Wu committed herself to this work in the midst of great political and personal turmoil. She had left China for graduate school at UC Berkeley**** in 1936. Only the following year, Japan invaded China, devastating Nanjing, then-capital of China, where Wu had earned her college degree. She lost contact with her family in China for the next eight years, remaining uncertain about their safety as the war in the Pacific came to involve the United States.

There are many fascinating angles on Dr. Wu’s life, but we’re here to talk about one of them: ambition.

In 1947, Wu and her husband, fellow physicist Luke Yuan, had a son named Vincent. Wu nonetheless maintained the relentless pace and total commitment to research that characterized her approach to physics before Vincent was born.***** She worked six-day weeks that included frequent late nights at the lab. According to Julie Des Jardins,

Wu often left her son with a nanny or fending for himself; graduate students admitted their discomfort when he called the lab at night to tell his mom that he was hungry and wanted her to come home, although most of the time she was too absorbed in experiments to heed him.

Wu and Yuan's son Vincent as a child in New York City.

Due to her exacting standards for graduate students and her perceived lack of maternal feeling, Wu acquired the nickname “Dragon Lady.”

The racist and sexist “Dragon Lady” stereotype dates back nearly a century, to the 1930s United States and particularly to a comic called Terry and the Pirates, where the phrase referred to the comic’s female villain. Contrary to another stereotype of meekness or submissiveness in East Asian women, “the dragon lady” is seen as aggressive, evil, or domineering.

Wu, in short, didn’t perform that delicate dance Romm speaks about in Double Bind: “success paired eternally with...retreat.” She didn’t moderate her intense devotion to research by taking on any trappings of domesticity in the lab or a nurturing role with her grad students.

As a result, she was met with stereotype upon stereotype. Dragon Lady. Battle-axe. Bitch.

For his part, Vincent Yuan, who would go on to become a physicist himself, doesn’t seem to rue his mother’s absences:

For her part, Dr. Wu would embrace the nascent women’s movement in the 1960s and ‘70s. In 1964, Wu presented at an historic MIT symposium on “American Women in Science,” alongside then 86-year-old industrial engineer Lillian Gilbreth. Seven years later, she participated in the first meeting of women in physics at the annual American Physical Society conference. After her retirement, she focused on the cause of recruiting and retaining women in physics. Wu called out the stereotypes that made women feel science wasn’t for them, and that discouraged their male peers from perceiving their worth.

In a sense, Wu’s later-life feminism was a return to her roots. Her father was an engineer who believed in equal rights for women. He delivered on that belief by founding the first school for girls in the region, then becoming its principal.

Admittedly, Wu’s notion of parity in the professional realm looks different than mine. As Des Jardins puts it:

Wu…did not seek to change the culture of the lab so much as to make women a part of it.

She enjoyed the relentless pace of scientific culture; the sacrifice of the personal sphere to the demands of discovery; the glimpses at beauty that such single-minded preoccupation enables. I believe, instead, that to retain more women in physics today, we need to change the culture of science as well. And on a personal level, I am searching for integration of the different pieces of my identity - the writer, the professor, the parent. But I also think Wu’s point of view (shared by some modern women as well) deserves to be met with respect rather than snide judgments or crude stereotypes.

Asymmetries persist – not only in the field of physics, where women continue to be dismally underrepresented.

We FIND asymmetry in the heightened scrutiny that accompanies the Ambitious Woman.

This scrutiny, whether of professional ability or personal choices, paradoxically interferes with our ability to see her. It prevents us from approaching her life, her creative vision, her decisions about work and motherhood, fully on their own terms.

NOTES

*Technically, asymmetry refers to a few different concepts in particle physics, but this is the version that's important for telling Dr. Wu's story.

**Later in life, Wu expressed regrets about being involved in a project that caused so much devastation.

***I'm calling out my alma mater here: Wu, one of the preeminent physicists of the time, worked at Columbia for over a decade before being offered tenure.

****She'd planned to enroll in grad school at The University of Michigan. But landing first in San Francisco from China, she was seduced by both the world-class physics program at Berkeley and by her future husband Luke Yuan.

*****Of course, the same could be said of her husband Luke, who (unsurprisingly) escaped similar scrutiny of his parenting skills.