“I don’t care when you do it, just teach this book.”

It was the last day of classes. The college freshmen in my American history course were discussing Rebecca Skloot’s non-fiction bestseller The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, which we had spent the last two weeks reading together. Some students chimed in that they would have liked to read Immortal Life earlier in the semester.

Regardless of the timing, my students were adamant that I teach Immortal Life again. Although I love the book, I was startled by the intensity of their response to it. There was clearly a hunger for these unheard stories, an urgency to reconsider whose history we tell, and, by extension, whose history matters.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, now an HBO movie, is the biography of Henrietta Lacks, a poor, black mother of five who died of cervical cancer in 1951 while being treated at Johns Hopkins University's “colored ward.” Taken without her permission and without her family’s knowledge, Lacks’ cancer cells led to the first ‘immortal’ cell line. Her cells, known as “HeLa,” generated countless medical breakthroughs as well as a multibillion dollar industry. Her name, however, was largely forgotten (or misremembered) until the 1970s, when journalists caught up with the story. It wasn’t until Skloot’s book came out in 2010 that a fully realized portrait of Henrietta and her family emerged.

Henrietta Lacks and Mamie Phipps were born just a few years apart but into seemingly disparate worlds. Lacks, born Loretta Pleasant in 1920, lost her mother when she was four years old. Her grandparents raised her on a tobacco farm in rural Virginia. In contrast, Phipps grew up in a decidedly middle-class nuclear family in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Mamie Phipps' father was a well-respected physician from the West Indies; her mother a homemaker who also assisted in her husband's medical practice.

Lacks barely received a sixth-grade education; Phipps Clark would become the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in psychology from Columbia. Despite these differences, their stories are bound up together as black women WHO CAME OF AGE in the Jim Crow South.

In an oral history conducted in the 1970s, Phipps Clark recalls hearing about a lynching in her hometown when she was six years old. She describes her childhood as “privileged” while also acknowledging that race was a constant presence in her life from an early age:

I think I became acutely aware of [segregation] in childhood, because you always had to have a certain kind of protective armor about you, all the time. You weren't suffering from it, but you had to be on guard all the time....

Clark and Lacks’ contributions to science both intersect with the story of race and racism in the United States. As Skloot suggests, the failure to honor Henrietta – and to inform the family of what happened to their mother’s cells – is tied to her lack of power, and to the racial biases that shaped medicine at the time.

Dr. Phipps Clark, meanwhile, conducted trailblazing social-science research on segregation and self-worth.

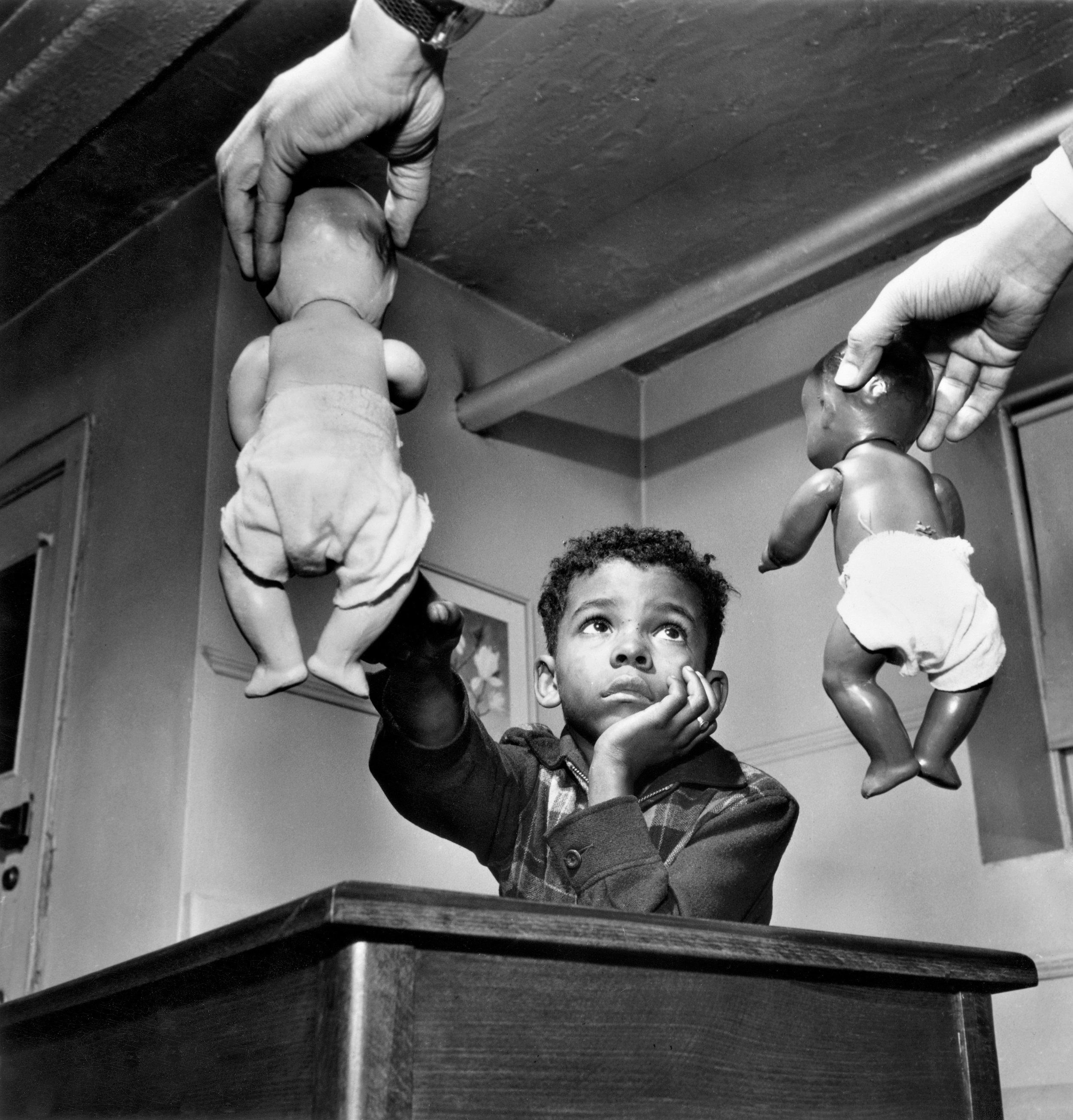

Images: Mamie Clark with husband Kenneth, also her research partner. A photograph of the Clarks' doll tests by Gordon Parks (1947).

Clark's 'doll tests', conducted with her husband Kenneth in the mid-twentieth-century, are still discussed – and sadly, still replicated – today.* The most famous iteration involved about 250 young black children aged 3 to 7, one half from a segregated school in Arkansas, and the other half from an integrated one in Massachusetts. After being shown four dolls (two with brown skin and two with white), they were asked to indicate the doll’s race, as well as which doll they would rather play with:

The Clarks’ doll studies and expert testimony influenced the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v Board of Education (1954), the landmark case that desegregated public schools in the U.S. The husband-and-wife team quickly became central figures in the civil rights movement.

Despite a 40-plus-year partnership (both romantic and professional), the Clarks found themselves on different career paths, based on the gender biases of the time. Even though the doll studies grew out of Mamie’s Master’s thesis, even though her husband insisted that he had “crashed” his wife’s research, the doll studies remain largely attributed to Kenneth. He would go on to become a professor at CUNY, while Mamie was unable to secure a tenure-track position. She would later describe herself as an “unwanted anomaly” in academia in the 1940s.

Together the Clarks opened Northside Center for Child Development, which offered psychological counseling and social services to children living in poverty in Harlem. Mamie served as Executive Director at Northside for over three decades. She retired in the late 1970s, and passed away from lung cancer only a few years later, in 1983.

I went into this post wondering about Dr. Phipps Clark’s experience of motherhood while working on such emotionally and mentally challenging research. What was it like for her to earn a trailblazing Ph.D. at Columbia – under an openly racist dissertation director, btw** – while giving birth to and raising two young children? How did her concerns for the physical safety and emotional well-being of daughter Kate and son Hilton fuel her broader work toward racial justice?

A rare glimpse of Clark's invisible motherhood. Clark pictured with her two young children while she was a graduate student at Columbia University (NCCD photo collection).

What I found, in answer to these questions, was mostly….radio silence. Unlike Lacks, who for decades was misremembered as “Helen Lane” or sometimes "Helen Larson,” Clark’s legacy has been kept alive. There are a handful of profiles of Clark online and in academic books. But we don’t know nearly enough. Clark deserves a full-length biography.

So, the story shifted.

Instead of diving into Clark’s personal life, I began thinking about the silences, the gaps in the historical record. Aside from the occasional blockbuster like Hidden Figures, how often are stories of African American women in science told in popular culture? And even more so, in ways that frame them not only as tough-as-nails professional pioneers, but as real, complicated, sometimes vulnerable humans?

This deficit of stories from the past also translates to an absence of representations of modern black motherhood in the present.

In “Ain’t I a Mommy?,” Deesha Philyaw remarks on the glut of motherhood memoirs and books on parenting, but in ways that often default to the POV of white, straight, middle-class mothers. Playing on Sojourner Truth’s famous nineteenth-century speech “Ain’t I Woman?” in which Truth staked her claim to a more intersectional feminism long before there was such a term, Philyaw calls out the corresponding lack of visibility for black mothers' experiences.

Philyaw goes deep into history to understand this phenomenon. On the one hand, black caregiving is everywhere in the racist iconography of slavery and Jim Crow, especially in the figure of the "mammy." At the same time, the archetype denies African American women's subjective experience of motherhood. She is visible only in relation to the white children she cares for.

Philyaw sees ripples of this history in contemporary culture - not just in the publishing industry's biases, but in black writers' own sense that their motherhood stories don't need telling. As one mother of two, with a law degree from Columbia, explained to Philyaw:

“I struggle with the daily demands of mothering. But I also remember that I’m standing on the shoulders of my great-great-grandmothers who were enslaved, beaten, raped, and they pulled through and made it. My existence is proof of their survival, their victory and perseverance. So how can I have a meltdown because my kid is having a tantrum when I’m trying to cook?”

I see an echo of this historical thinking in an anecdote Kenneth recounts about Dr. Phipps Clark. He asked her once why she never wanted to entertain, was never interested in 'keeping up with the Joneses.' She replied, "Kenneth, we are the Joneses." Her childhood in segregated Arkansas, her career-long proximity to childhood suffering and poverty, had sharpened her awareness of her privilege and - despite the social obstacles she faced - of her power.

The disorientation, the disruptions, of being a parent can lead us to operate in crisis mode. We seek refuge in the familiar. We hug our narrow worlds and viewpoints closer. But those Moments of Weirdness that we encounter when interacting with small children can also be opportunities. They can push us to become more thoughtful parents, creators, and human beings. They can allow us to notice – and seek to address – our preconceptions and our blind spots.

I’d been 'simply following my curiosity' when choosing who to profile on this site, but this curiosity had been leading me overwhelmingly to stories of white, straight women. Nine months into writing this blog, Dr. Phipps Clark is the first African American scientist I've profiled (aside from a brief fangirl-ish bit about Dr. Mae Jemison). I need to – and want to - GET CURIOUS about people’s stories of caregiving that don’t map neatly onto my own experience.

Thirty-five years after her death, Dr. Clark’s bias study continues.

NOTES

*For more on the Clarks' doll studies and their continued relevance, see Janet Stickmon's article on seeking (non-sexualized, empowering) black dolls for her daughter. In the essay, she references the Clarks’ study. Actually, just check out her entire clever and funny HuffPo series, titled "Letters to Black Parents Visiting Earth."

**In another school-desegregation case leading up to Brown v. Board of Ed, Clark actually took the stand to rebut the testimony of her former advisor, Henry Garrett, who believed in innate racial difference.