“After the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?”

- Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Manifesto for Maintenance Art

“Garbage in, garbage out.”

- Computer Science term attributed to Stephen Wilfred Hey

1. Department of Sanitation

The first time I heard of the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, I straight-up laughed.

“Listen to this,” I called out to my husband as he puttered around the room getting ready for bed:

We both chuckled. It was admittedly a kind of philistine moment, where you look at a work of modern art blankly, uncomprehendingly. And, failing to “get it,” you react by poking fun.

But then I turned the page (or rather, touched the screen on my e-reader), and was instantly chastened:

Oof.

Recognition quickly replaced my earlier bafflement. I felt some embarrassment, warmth. As if I’d just told a joke at my own expense.

2. Maintenance Art

In 1968, Ukeles gave birth to the first of her three children. She had moved to New York from Denver a decade earlier to pursue an art career. She now experienced the roles of artist and mother as warring sides of a double self:

She was also struck by the lack of curiosity around her experience of new motherhood, an indifference to parenthood’s mundane and sublime moments. She recalls, “When people would meet me pushing my baby carriage, they didn’t have any questions to ask me. They didn’t say, ‘How is it, to create life?’”

Aside from what she described as this cultural “muteness”—the lack of language for talking in a nuanced way about motherhood—she balked at the invisibility of her daily labors, the “washing, cleaning, renewing, supporting, preserving, etc.”

These disparate influences converged, gathered force and clarity, in Ukeles’ 1969 art manifesto—furiously typed at a rickety office desk while she, husband Paul, and their young daughter were living in Philadelphia for the year.

Ukeles’ path toward wholeness was to redefine what constituted ‘art’ in the first place. Her flash of insight came when she realized, “I have the freedom to name maintenance as art. I can collide freedom into its supposed opposite and call that art. I name necessity art.”*

Ukeles coined the term “maintenance art” to take those invisible, life-sustaining tasks and “flush them up to consciousness, exhibit them, as Art.” Later, Ukeles would describe maintenance as a way of getting attuned “to the hum of living. A feeling of being alive, breath to breath.” Without discounting the boredom and repetition in such work, she insists that maintenance is a crucial “part of culture. Because if isn’t, then you don’t have a culture that welcomes in everybody.”

In pieces like “Dress to Go Out/Undressing to Go In” (1973), Ukeles documented her everyday labors within the domestic sphere. But these acts were a small facet of her much larger canvas, a continuum of maintenance work that stretched from the personal through the “social, planetary.”

What fascinates me is how Ukeles responded to the challenge of those early parenting years. She could have made art that looked inward, that ‘elevated’ the domestic realm into a space of artistic inspiration and expression. Like the prom dress Joanne Lyons stitched for her daughter, repurposed into a museum piece. Or Sally Mann’s lush, provocative, gothic-inspired photos of her three kids, taken when she no longer had the flexibility to shoot photographs out in the world.

Instead, Ukeles widened her gaze. She glimpsed how the small, routine acts that nurtured her family and kept her household running fit into a larger, interconnected whole. Her artistic vision extended outward from the home, to the jobs that keeps our communities running, functional, living. She forged strategic alliances, broadened the circle of whose caregiving work her art would make visible. Her own labor in the home became a departure point, a node in a network connecting ‘women’s work’ with the labor of working-class men, of people of color.

And with the life-sustaining work of the natural world. As Ukeles would later recall, “Even in the beginning, I always thought about scale: personal, social, planetary. Work doesn’t exist in a vacuum.”

Right from the start, Ukeles messed with the boundaries between private and public, troubled deep-set divisions of class and color. Her manifesto included a proposed exhibition, “CARE,” in which she would perform her daily caregiving work for her family in the public space of the museum: “I will sweep and wax the floors, dust everything…cook, invite people to eat…. My working will be the work.”

But Ukeles didn’t stop there. She imagined an aspect of “CARE” that included typed and exhibited interviews with workers of all occupations, asking them “what they think maintenance is…what is the relationship between maintenance and life’s dreams.” Ukeles also included “Earth Maintenance” in her proposal. She wanted to make the pollution of the air, land, and water visible, concrete, and to interweave it with these personal and social forms of maintenance. Although this art show was never staged, components of these ideas would find their way into her later projects.

Just as Ukeles brought private domesticity into the public sphere, her art often invested public maintenance with a nurturing, even feminine quality. Although Touch Sanitation Performance had Ukeles shadowing sanitation workers in 8- to 16-hour shifts all over the city’s five boroughs, her ritualized phrase of gratitude cast their maintenance work as simultaneously intimate, individual. “Thank you for keeping New York City alive,” she told each of them. As if one of the greatest metropolises in the world were a fragile newborn, demanding daily sustenance, in need of attentive caregiving.

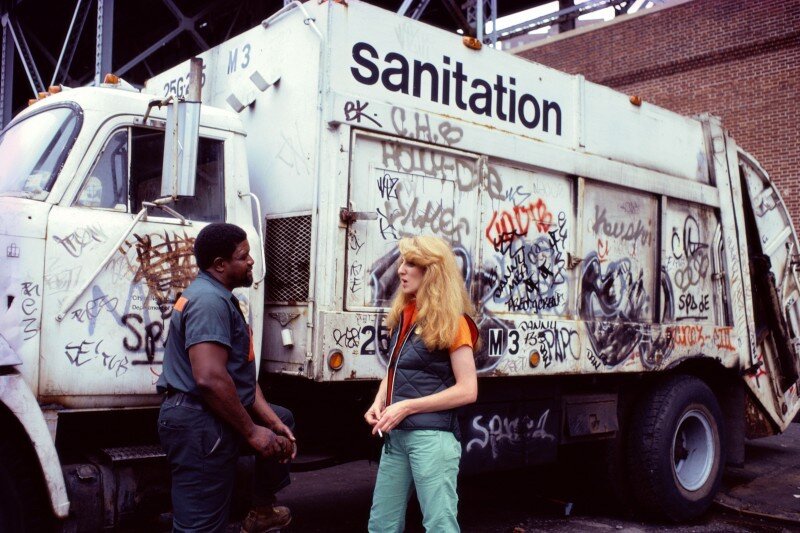

A few images from Touch Sanitation Performance (1979-80).

…

I had initially dismissed Ukeles’ preoccupation with maintenance work as a gimmick. (To be fair, her collaboration with the NYC Sanitation Dept. did have its origins in a joke of sorts.**) But what quickly made my early laughter so uncomfortable was that it revealed my own failure of imagination. I’d failed to envision how maintenance work could be worthy of art, could be art.

Art graces us with new eyes; it hones our senses so that we can approach the world with a heightened awareness. Art is an angle onto the overlooked.

Ukeles’ body of work takes this premise to its logical extreme. What could be a more fitting expression of art’s transformative power—its ability to imbue the devalued, the discarded, with meaning—than to make art out of literal trash? And, more crucially, to claim those practitioners of maintenance work—the housewives, garbage collectors, custodial staff—as the artist’s worthiest subjects?

3. Garbage In, Garbage Out

Ukeles, in short, began with the personal and the domestic. But she quickly expanded her scope to cities and systems before arriving at an ecological perspective, a planetary consciousness. Decades before the Green New Deal entered the political lexicon, Ukeles’ art manifesto linked environmental justice with problems of invisible and low-status labor (“maintenance jobs=minimum wages, housewives=no pay”). She might have peppered her analysis with sixties slang like “Maintenance is a drag” and “keep the contemporaryartmuseum groovy,” but the ideas sound current.

Given this context, it’s no surprise to hear that Ukeles’ latest art project is situated on Fresh Kills, the former Staten island landfill that was once the largest in the world. In operation from 1948 to 2001, Fresh Kills is now undergoing a massive transformation into a public park, art space, and wildlife preserve. Ukeles herself has been advocating for this park since the late 1980s, and she will contribute to its first permanent art installation. LANDING will invite visitors to orient themselves in the landscape from three different perspectives: “perched and floating (Overlook), standing solidly on the land itself (Earth Bench) and being within the land which becomes a sheltering refuge (Earth Triangle).”

In the spirit of massive Land Art projects by Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer, LANDING also departs from these works in its accessibility to urban visitors and, above all, by bringing the messy human component into the rehabilitated landscape. While the scale has changed, these new land-art installations riff on her earlier works, like 1983’s The Social Mirror. A decommissioned garbage truck covered in hand-tempered mirrors, this mobile art exhibit “allowed citizens to see themselves linked with the handlers of their waste.” Similarly, Ukeles reminds us, “All of us made the social sculpture that is Fresh Kills.” Having lived in Manhattan in the late nineties and early aughts, I am aware that Ukeles’ latest maintenance-art project includes, and implicates, me.

…

On the eve of Earth Day 2020, Ukeles’ maintenance-art manifesto takes on an even greater necessity than it did fifty years ago, as the very first Earth Day was being planned. Rather than placing nature outside of culture, Ukeles argues for their deep-rooted interdependence. Her work raises questions of perspective, artistic and ethical; questions about who and what matters; questions of value.

Computer scientists have this concept of “garbage in, garbage out”***: the idea that faulty, nonsensical, or shoddy inputs into a system will invariably generate low-quality outputs. Today, there’s a dawning awareness that the edifices of our modern economies—our food systems and energy sources and infrastructure—have been built on trash inputs, literal and figurative.

As Mierle Laderman Ukeles, that unsalaried artist-in-residence with NYC’s Sanitation Department, has been showing us for half a century: it’s garbage all the way down.

…

Maintenance art inverts the established hierarchies. It has this carnivalesque quality, the world turned upside down. Our culture values the new: the people who stand out, excel, achieve, innovate. Tech culture, entrepreneurial culture, are all about “disruptors”—the opposite of continuity. The word abiding, in contrast, calls to mind a kind of a slacker ethos—e.g., coasting, “the Dude abides,” a perpetual adolescence.

Ukeles, in contrast, questions our ranking of an individual’s inventiveness above our collective sustenance. She associates the avant-garde in art with “The Death Instinct: separation, individuality.” She opposes this to “The Life Instinct,” responsible for “the perpetuation and MAINTENANCE of the species.” While development systems reward “pure individual creation; the new; change; progress,” Ukeles argues for the equal necessity of maintenance systems, which “preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress.”

Ukeles’ The Social Miror (1983), a mirrored trash truck turned mobile art exhibit.

Ukeles’ distinction between these life and death drives in our art and culture came to mind while reading Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes from a Catastrophe, an influential early book on climate science. After years of journalistic research, Kolbert offers a devastatingly clear-eyed assessment of our current situation:

She argues, in other words, that our civilization, our species, has set ourselves on a trajectory toward suicide. Remember that climate change, too, is a disruptor—of food chains, migratory patterns, ecosystems. Like the economic systems that fuel global warming, it prizes rapid growth, hasty adaptations, unprecedented risk.

…

In Jenny Odell’s How To Do Nothing—the book that introduced me to Ukeles—Odell cites this passage from environmental-law professor Jedediah Purdy.***** Like Ukeles’ manifesto, it connects the dots between caregiving in the home, maintenance work in the public sphere, and equilibrium in the natural world:

We have historically discounted the labor of nurturance: the diapers washed, the meals cooked, the sick and elderly tended to, the floors swept, the trash can hauled to the curb. These repetitive, often monotonous tasks are nonetheless crucial, life-affirming acts.

So, how—in this pivotal moment for our species—do we make the cultural shift toward valuing maintenance work, which, with belated clarity, we realize is just another name for survival?

4. Maintenance Work

After I’ve clicked “scheduled” on this blog post, after I’ve closed my laptop and pushed my chair away from the desk, I’ll get to work. If it’s Thursday, I’ll slip on my sneakers and drag the compost, recycling, and trash bins to the curb. Then I’ll do the same with my elderly neighbors’ bins. I’ll remember the compost bags are still in the freezer (shit—I always get that out of order), so I’ll take off my shoes, grab the compost, put on my shoes again while cradling the food-waste bags against my chest (gross) and jog out to the sidewalk. When I return indoors, our cat will greet me at the entryway, complaining, so I’ll follow her to the kitchen.***** After scraping some wet food into her bowl and sprinkling it with a probiotic, I’ll start dinner: press tofu, chop chard, blitz together a sauce, boil water for soba noodles. I’ll wash the dishes and set the table during any pauses in the cooking. Upon returning home, my 4-year-old will call out “MOMMY!” at the top of his lungs, while my husband trails behind him burdened down with the backpack and the lunchbox and All the Stuff. Spatula in hand, I’ll race to the door to unlock it and greet him. He’ll enter the household flinging his dirt-filled sneakers into the shoe bin and launching immediately into some playground anecdote or petty complaint or dreamlike vision for his next art project or incoherent monologue in “turtle language.” Eventually, I’ll steer him toward the bathroom for hand-washing. At dinner, I’ll sit down to eat only to realize his water cup is empty. I’ll get up again to grab his multivitamin. Then to fill his sippy cup a second or a third or a fifth time. If it’s my night for bath duty, I’ll cajole him into taking off his clothes while my husband starts on the dishes. I’ll fill the bath, then draw on all of my remaining creative energy to cajole him into it. Pour water over his head, scrub face, neck, armpits, butt, while he wriggles away from me, in the midst of deep pretend play. Cajole him out of the bath now. Towel him off. Carry him—he still insists on being carried—into his room where he’ll prance around wildly, in that manically overtired state before sleep. Each article of clothing will take an eternity to add to his person. Books, toothbrushing, songs. Blinking into the hallway light outside of my son’s darkened bedroom, I’ll return to the kitchen to pack his lunchbox, to brush crumbs from the dining-room table. The cat will meow again, and I’ll head to the fridge to replenish her bowl. Having told the final bedtime story, my husband will join me on the couch. Every inch of our tired middle-aged bodies and depleted brains will want to Netflix and chill, but instead we’ll begin our weekly “temperature report,” a maintenance routine for our marriage. We’ll coordinate the next week’s schedule, troubleshoot any household tasks or relationship challenges, as we fold the previous night’s load of laundry. Then I’ll pack up the folded clothing, settle each item neatly into the basket. (I don’t know why I am so gentle with the laundry, smoothing down each small pile of clothes with a mother’s caressing touch.)

Will Ukeles’ manifesto help to alleviate any of the boredom or frustration or sluggishness I feel as I go about my business, during those hours for daily maintenance work between 5 and 9 pm? Doubtful.

But maybe, seeing through Ukeles’ eyes, I’ll take a minute to express gratitude for the City of Austin Resource Recovery workers who will arrive early the next morning to haul away our household waste. To picture them a bit later on their route, when they drive past my son’s neighborhood preschool. Without fail, they’ll honk the truck’s horn to the delight of the gathering children. In that simple act of kindness, they will blur the lines between sanitation work and care-work, reveal that both jobs, despite their historically rigid gender associations, are part of the same life-giving fabric.

Or maybe, as so often happens, I’ll forget to be grateful.

Surely, though, I’ll whisper this mantra under my breath, borrowing the words Ukeles invented to cure a culture of its mute inattention to the laborers, human and nonhuman, who maintain equilibrium, who sustain life:

“I am doing maintenance work.”

Ceremonial Arch IV (1988/1993/1994/2016).

ACTIONS

I wrote this post before we were all thrust into a global pandemic. Originally, I’d planned to urge you to attend one of the three days of Earth Day strikes and actions being planned around the world from April 22nd through the 24th.

Things look radically different now. But while our strategies and even our priorities must adapt, we still need to keep the climate conversation going. A simple entry point: follow the Fridays for Future #digitalstrike or #climatestrikeonline hashtag on social media, or consider making a Friday climate post of your own. Reach out to a climate-focused organization like Sunrise, 350, Citizens’ Climate Lobby, or Extinction Rebellion to find out what your local group has planned. If you are a parent raising young kids or teens right now, subscribe to Mary DeMocker’s newsletter for advice and inspiration.

NOTES

*Ukeles has been criticized for having the privilege, as a white middle-class woman with an art degree, to make such a declaration, in contrast to many of her subjects. A fair criticism. But Ukeles was, and is, hardly a mere class tourist. She has now been an artist-in-residence with the Department of Sanitation—whose offices, along with Ukeles’, are housed in Lower Manhattan—for over forty years. Ukeles is deeply familiar with the Department’s inner workings, having outlasted seven commissioners.

**Here’s the backstory behind Ukeles’ Sanitation Department gig:

***In the U.K., the phrase is modified to “rubbish in, rubbish out.”

****I wrote this passage before our cat passed away suddenly, and now I’m feeling guilty about the grudging way I used to care for her.

*****I recently came across a panel discussion with Purdy about a month after he became a new father. He seems particularly aware of how his academic credentials have left him unprepared to grapple with climate change from the more experiential perspective of parenthood. Purdy confesses,