Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers; Little we see in Nature that is ours; We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

- William Wordsworth, “The World is Too Much with Us”

I’m poor as a mouse,

I’m richer than Midas.

But nothing on earth

Could ever divide us!

And if tomorrow,

I’m an apple seller, too,

I don't need anything but you!

- “I Don’t Need Anything” from the musical Annie

1. Zombie Housewives of the World, Unite!

Have you seen the movie Tampopo?

It’s this Japanese cult classic from the ‘80s, a campy, loving homage to Japanese comfort food, from ramen noodles to omuraisu. Through a series of food-centric vignettes, narrated by a yakuza epicure, the film explores the complex ways that what we eat, and what we crave, intersects with culture, sex, violence, nostalgia.

This one scene from the film keeps replaying in my head lately. A housewife rouses herself FROM HER DEATHBED to cook one last dish for her family.

We first see her husband racing home, his frantic energy in stark contrast with his wife’s torpor. While a bearded, Freudian-looking doctor observes them dispassionately, the husband shouts commands to his wife to cling to life.

Finally, the order “Get up and cook! Go get dinner ready!” does the trick. She staggers, hunched, toward the kitchen while the kids set the table and her husband watches her work. After setting the wok on the table, she wears the beatific smile of a Madonna before collapsing lifeless to the floor. Her three kids start keening with grief, but the husband continues to shovel food into his mouth, shouting at them to keep eating while the food is still hot: “It’s the last meal Mom cooked.”

That domestic tableaux—both humorous and horrific—visually encapsulates the absurdity and exhaustion of parenting-without-the-usual supports during this past year. A year that makes me want to pose this question to Santa—or rather, to howl it, Maria Von Trapp-style, from the mountaintops:

Where is my reward?!

The dying housewife scene in Tampopo, just before the wife (pardon the pun) ‘goes to her reward.'

2. Home Economics

Before we begin, a confession: I’ve tried, and failed, to write this post on the “rewards of parenting” a few times before. It seemed both too abstract and…well…too whiny.

It still does. I know, deep down, that out of this slag-heap of a year, I’ve emerged as of the fortunate ones. But as we parents lurch into the final days of 2020, like a legion of zombie housewives from Tampopo, the time has come to revive the topic. If ever there was an excuse to kvetch a bit, this is it.

Also, there’s nothing like a world turned upside down to get us questioning the received wisdom. And one of the most tenacious, if empty, truisms in the modern cultural consciousness is this: that parenthood is supposed to be “rewarding.”

This essay is not really about the private struggles of this year, real, and keenly felt, as they are. It is about economics. About the power of metaphor. About systems of value and how they fail to account for the labor of nurturing young life.

…

A couple years back, the podcast One Bad Mother did an episode calling BS on the phrase ‘rewards of parenting.’ As co-host Theresa Thorn asked (rhetorically): do we really do everything we do for our children to be rewarded? And if so, what the hell are those rewards? Do they actually compensate us for all of the sleep deprivation and interminable whining and denial of self that we endure?

Underlying, or alongside, the comedic treatment, the episode offered a serious takedown of a capitalist framework for viewing our caregiving roles. Raising a child is not a transaction. It certainly does not bring us wealth, or elevated status, or first-prize ribbons.

Anyway, the show made me want to dig a bit deeper into the origins of this phrase. When did we begin conceptualizing parenthood in terms of ‘rewards’? And what other metrics, other metaphors, might we use to make sense of the caregiving role?

3. The Parenting Trap

My guide on this quest was the psychologist and philosopher Alison Gopnik. Her latest book, The Gardener and the Carpenter, contrasts these two models for viewing our role as parents. A carpenter molds, builds, constructs a ‘better’ (or at least more socially acceptable) human according to a pre-arranged plan. A gardener nourishes and cultivates, leaves space for whimsy and randomness, fully aware of our lack of control when interacting with the natural world.

Gopnik’s theory of how generations propel social change suggests that we all benefit when we approach parenthood like gardeners: when we leave open an element of risk and unpredictability as a means not only for enabling the individuals in our care to flourish but also the society as a whole to evolve.

Alongside her critique of the carpenter model, Gopnik takes issue with the use of a parenting as a verb. The term arose in the 1970s, and while exported elsewhere, it has a uniquely American cast in its emphasis on individual ‘bootstrapping’ versus collective responsibility for childrearing. It glosses over millennia of alloparenting: raising children in small groups with an extended network of caregivers who could provide resources and attention.

Gopnik believes that the verb tempts us to imagine that, if we work hard enough, we can acquire ‘expertise’ or achieve ‘success’ in child-rearing. It is fundamentally a business model for raising children:

On an individual level, this attitude results in unnecessary pressure to parent correctly and causes domestic tension when our efforts are not ‘rewarded’ with the expected outputs.

On a societal level, it creates an intensive parenting rat race for caregivers at all income levels, of which 2019’s college-admissions scandal was only the most ignominious and extreme example. It also absolves our policy-makers and institutions of the imperative to act.

And on a linguistic level, it shows that we have, like Midas, turned our most priceless relationships into gold:

Gopnik’s attention to language made me realize that I had been approaching this topic the wrong way. I was focusing on the why (as in, why do we do so damn much for our kids—biological drives? Social norms? ‘Love’ or whatever?) rather than the how (i.e., how do we as a culture talk about parenthood?)

It was a question not of motives but of metaphor.

4. Rational and Transactional

In Metaphors We Live By, cognitive linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson put the lie to the notion that metaphor is merely window dressing, a means of fancying up one’s prose. Instead, they argued that metaphors are central not only to our communication but to our behavior and our thought processes. Metaphors do not belong only to the peripheral realm of the poets; they have the power to shape our realities.

Lakoff and Johnson came to mind as I listened to Gopnik in conversation with Krista Tippett. They were discussing (among many other things) how Western philosophy has framed our ethical responsibilities to each other in terms of the contract. As Tippett summed it up, such a view reduces our human relationships to the “rational and transactional.”

Gopnik goes on to describe alternative ethical models, going back to the Chinese philosopher Mengzi, who pointed to the relationship between mother and child as a paragon for social relationships. In this system, “you take on the needs and utilities of that other person; literally, if you’re caring for a child, the child’s needs become your needs and often overwhelm your needs.”

For Mengzi and others in the Confucian tradition, “the real political problem is, how do you scale up (that close, intimate relationship) to the scale of a community or a nation or a planet?”

That felt, unshakeable knowledge of a child’s value—for Gopnik, that’s when we are actually “seeing people clearly,” really intuiting the value of living beings. We might joke that we are deluded when we revel in our particular child or grandchild or niece’s extraordinariness, wearing the rose-colored glasses of besotted relatives. Rather, Gopnik insists, “the illusion is when we think that there are billions of people who don’t have that worth, who don’t have that value, who aren’t that deep and important and worthy of love.”

This notion astounded me: that the parent-child bond, the caregiving role, could serve as the basis of a radically different way of doing our ethics and economics and politics. Gopnik speculates that parents, mostly mothers, have historically been too busy, too caught up in those practical, daily acts of caring for others to theorize about the wider scope of their labor, to limn its ethical and even spiritual implications.

I found this book recently at a free library in our neighborhood, but started getting jittery reading it.

5. Show Me the Money

Of course, by asking what the language of capital is doing in our discussions about raising children, I don’t mean to wave off our need for cold hard cash. The “getting and spending” of everyday life is hardly beneath the concerns of the Altruistic Parent. Far from it!

In fact, what’s so insidious about how the language of markets permeates the realm of parenting is that it masks the invisibility of childcare to actual markets. The more we internalize this rhetoric of parenting as a job at which we must strive to excel, the less attention we pay to it (and the less value we afford to it) in the wider sphere.

It’s not surprising, then, that there has been a movement to attach wages to caregiving and other unpaid housework, much as economists have attempted to reckon the hidden costs of environmental degradation. Even though I’m ambivalent about what we lose in translation, I realize that converting something to its dollar value is the only way to make it visible to a culture so steeped in commerce.

…

Two final thoughts on how this nexus of childcare and economics is playing out during the pandemic.

First, there is the way mothers in particular have stepped up these past months to bridge the gap between school closings and workplace demands. As economist Nancy Folbre quipped on Twitter, “Mothers as fallback, backup, safety net, and subsidy. But by conventional economic accounting measures, they contribute nothing.”

The costs of this mass exodus of women from the workforce have been discussed elsewhere, but I especially appreciated Katherine Goldstein’s piece for Romper, which zeroes in on the language we use to cover these stories, as well as the underlying cultural assumptions this language both reveals and propagates.

Goldstein takes issue with how media outlets like The New York Times, CNN, CNBC have used the phrase “drop out” to characterize how this year’s recession has disproportionately impacted women, especially women of color:

It is of a piece with the parenting-as-verb ethos that Gopnik dismantles, feeding into the same pressures on individuals to ‘figure it out,’ without acknowledging the larger contexts and social supports we might need to thrive as parents and workers. Goldstein demands that we tell a different story, one that enables system change, and that begins with attending closely to the words we choose:

…

Another piece of this story is the financial insecurity of childcare professionals, the disconnect between the dismally low wages and health risks for care workers juxtaposed with the high cost of care for parents who work outside the home.

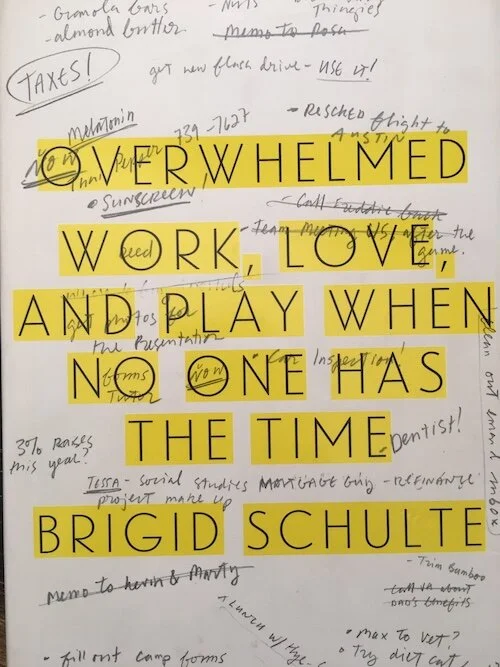

As Brigid Schulte notes, “In the United States, child-care workers earn roughly what parking lot attendants and bellhops do.” Meanwhile, daycare costs in some cities cost as much as rent or mortgage payments. The ledgers of our current system simply don’t add up.

Stable, safe, reliable childcare—already tenuous before the pandemic—has now slipped from the grasp of even some of us with the means to afford daycare. And yet, quality professional care hugely benefits both kids and their parents —something, by the way, we Americans knew way back in 1971, when a bipartisan bill for universal childcare nearly became law.

Schulte writes, “Researchers have found that parents with stable child care are less stressed, better at coping, and more satisfied with their jobs….” Additionally, “Formal child care, more than any other arrangement save shift work, leads to more gender equity at both work and home for both mothers and fathers.”

The movement for universal childcare has never had more urgency, and it is gaining momentum in the United States. I was heartened to learn that this November, albeit drowned out by all of the noise and strife of election season, a ballot initiative for universal preschool quietly passed with majority support in Portland, Oregon and the surrounding Multnomah County.

We can build on this foundation, but it will require diverse coalitions of working parents and professional care workers fighting side-by-side for large-scale change. It will ask us, in Gopnik’s words, to see people clearly. To know their worth.

6. Getting and Spending

Among the many items on my wish list for a post-pandemic world, is this: a new language for valuing the caregiving role. One that enables us to both enact the policy changes that will support parents and dignify the profession of childcare while acknowledging what is incalculable, what is sacred, about the bonds we develop across generations.

In the meantime, the hustle continues. I keep longing for the new year with its usual associations of renewal and optimism, as if somehow on January 1, 2021 I’ll uncover some hidden cache of energy and creative mojo.

Instead, winter looms. Come January 5th, when online kindergarten begins again, I will drag myself out of the bed where my 5-year-old bounces with manic disregard for our tired middle-aged bodies, make a pot of coffee on autopilot, and shuffle into yet another month on the sped-up, surreal assembly line that our home has become.

America, I’m putting my zombie-housewife shoulder to the wheel.