“I am happy to know a brave person like you, Toad,” said Frog. He jumped into the closet and shut the door.

Toad stayed in the bed, and Frog stayed in the closet.

They stayed there for a long time, just feeling very brave together.

- Arnold Lobel, Frog and Toad Together (1972)

I.

One of the delights of caring for a young child is the chance to revisit the lost world of picture books.

Sure, I have struggled through plenty a plotless alphabet book or Dr. Seuss wannabe full of hackneyed rhymes. But for every Batman is Fast! early reader that has inexplicably captured my kid’s imagination, I have found salvation in a Mustache Baby or a Captain Najork and His Hired Sportsman or a Weslandia. Books that, respectively, delight in the weird, make language their playground, or insist on the defiant beauty of outsiders.

As we transition into adulthood, most of us lose touch with how strange childhood can be. We forget its dark poignancies in the wake of showier adolescent dramas. Similarly, we might easily overlook the imaginative range and emotional register of children’s literature once the age for books-with-pictures-in-them has passed.*

Parenthood, however, provides us with a golden ticket back to that vivid, inventive, wondrous Technicolor world of picture books. Of course, we experience these books differently than we did as children, differently than our own kids do each night as they settle a bit deeper into our laps. But the feeling is no less magical for being tinged with an extra layer or two of knowingness.

At their best, children’s books are not didactic instruction manuals for how young people ought to be in the world. Instead, they serve as rabbit holes down which we can travel into the personal, and collective, id.

Perhaps, then, it’s fitting that many of the most innovative and influential children’s book authors of the mid-twentieth-century—from Margaret Wise Brown and Maurice Sendak to Tomie dePaola and Louise Fitzhugh (of Harriet the Spy fame)—were queer.

Jesse Green suggests that the genre became

Children’s fiction was powerful precisely because, in that pre-Stonewall era, it required authors to transmute subterranean desires, underground impulses.

Father-of-two Arnold Lobel, who authored and illustrated the beloved Frog and Toad series, reflected on this particular challenge of writing for kids:

Lobel never spoke or wrote explicitly about being gay. But the passage above might have gestured, albeit cryptically, to his closeted sexuality. Decades after her father’s death at age 54 due to complications from AIDS, Lobel’s daughter Adrianne would surmise that “‘Frog and Toad’ really was the beginning of him coming out.”

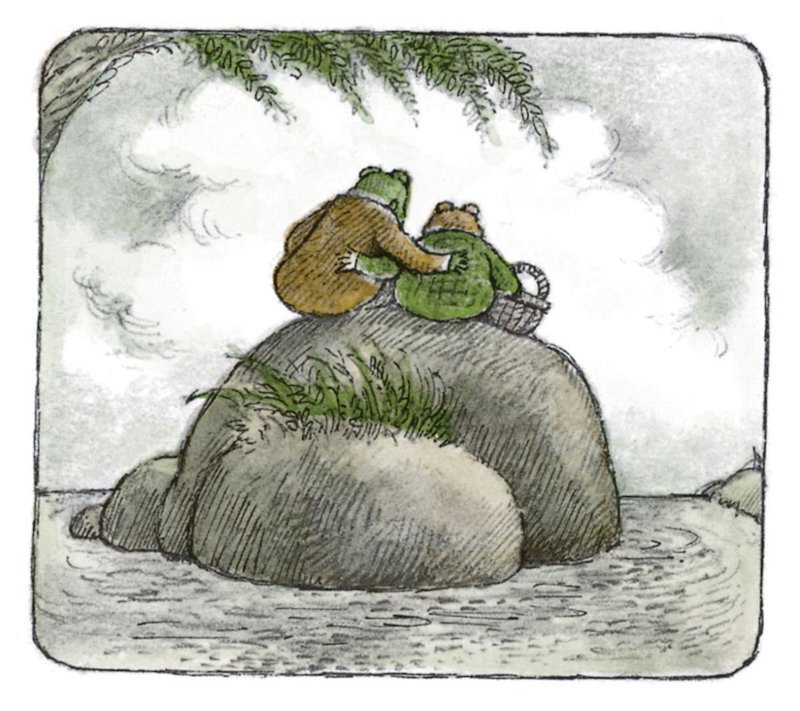

The series offered a brave, melancholic, and tender portrait of same-sex love, hiding in plain sight.

“They were two close friends sitting alone together.” The final illustration in Lobel’s Days with Frog and Toad (1979).

II.

Why is it that each year, as Valentine’s Day approaches, my thoughts take a decidedly unromantic turn? In the first year of this blog, I winced through research on psychologist Harry Harlow’s heart-breaking rhesus monkey experiments, which showed the necessity of the parent-child bond—and the devastating effects of its absence. In the second, I watched, transfixed, as the marriage of evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis and science popularizer Carl Sagan imploded.

And now, the tragicomic relationship of two odd-couple amphibians, wistfully imagined by a closeted children’s book author.

Maybe I’m possessed by a rebellious inner spirit who delights in plumbing the razor-sharp edge of sadness behind vapid commercial holidays. Or, maybe the Ghost of Lonely Eileens Past rears her head each year for one vengeful February haunting.

Either way, I’m reminded of a recent planning meeting for our non-profit science communication group, where one Board member made the gleefully contrarian suggestion to schedule a talk with a feral-pig expert for smack in the middle of February. Never mind such clichéd topics as the chemistry of chocolate or the role of pheromones in mate selection.

Happy Valentine’s Day. Cue the feral pigs.

III.

Or rather, cue the domesticated amphibians? The seeds of the beloved Frog and Toad early readers were planted in childhood: on summer vacations in Vermont, the young Lobel kept frogs and toads as pets. More generally, his turn toward art was bound up in a lonely (and somewhat sickly) childhood.** Having missed most of the second grade due to illness, he made tentative gestures of friendship toward his classmates by gifting them his animal drawings.

In 1954, Lobel met his future wife Anita Kempler, a fellow art student at Pratt. A Polish-born Holocaust survivor, Kempler had her own fascinating backstory. After their daughter Adrianne and son Adam were born, Lobel and Kempler both decided to pursue careers in children’s literature, independently and as collaborators. They shared studio space above their Brooklyn home, where they continued to work side by side for years after Lobel came out to his family.

Lobel got his start in 1961 as a children’s book illustrator for Harper&Row. The following year, they published A Zoo for Mr. Muster, the first book Lobel authored and illustrated. But it was the four Frog and Toad books, whose publication spanned the ‘70s, that cemented his legacy.

The timing is curious. Frog and Toad are Friends appeared in 1970***, a year after the Stonewall Inn riots that ushered in a new era of ‘outness’ for the LGBTQ+ community. For Lobel, though, the movement’s iconic chant—“We’re here. We’re queer. Get used to it”—was more of a whisper (or croak) of quiet protest:

Regardless of the extent to which Lobel consciously represented his sexuality on the page, the Frog and Toad series explored deeply personal terrain. According to Kempler, “the Frog and Toad books were the first that Arnold ‘felt very deeply. He was not just manufacturing stories…he was talking about important subjects like friendship, fear, loneliness, hysteria, doubts, psychosis.’”

As Lobel, that author-animal or animal-author, put it, “Frog and Toad are really two aspects of myself.”

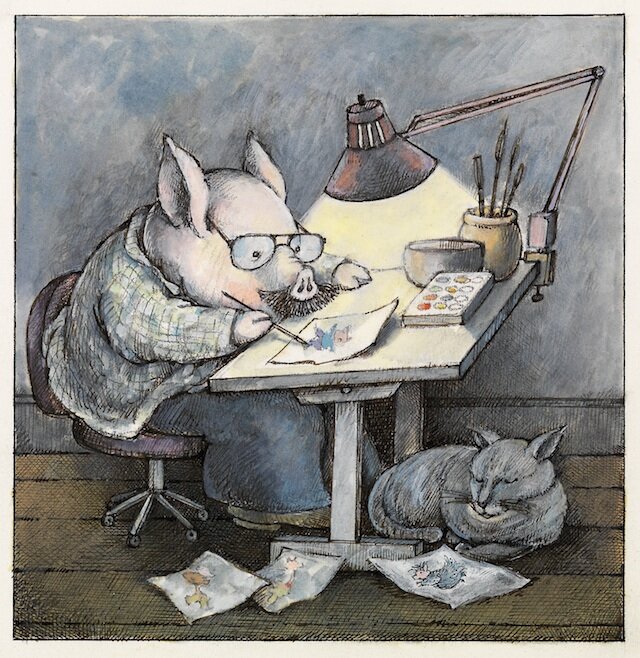

Arnold Lobel, “There was an old pig with a pen,” from The Book of Pigericks (1983).

IV.

Aside from that lone anecdote, I had trouble finding Lobel the Father in the research materials available online. In one interview, Lobel confessed that “I've never been able to give a satisfactory answer” to the question of fatherhood’s role in his creative process. He settled for this perfunctory response: “Certainly being around children and knowing a child's sense of humor is no detriment.”

As with Samuel Delany, the last father I profiled here, it’s difficult to find clues from interviews or biographical sketches. We need to turn to his fiction.

Let’s begin with another of Lobel’s beloved early readers: 1981’s Uncle Elephant. In the book, a young elephant’s parents are believed to have died in a shipwreck. His “bachelor uncle” (euphemistically so?) arrives to retrieve and care for him. On the train journey to Uncle Elephant’s house, Uncle Elephant tries counting the houses, fields, and telephone poles as the train zooms past, but he can’t keep up. So, he finally settles for counting the shells of the peanuts they snack on during the trip.

Toward the end of the book, the two elephants receive word that the child’s parents are in fact alive, so they make the return journey. In a neat symmetry, Uncle Elephant begins counting once again, only this time mysteriously so. As he says good-bye to his nephew, he asks him to guess what he had been counting on the train:

Before I fell asleep. Uncle Elephant came into my room.

"Do you want to know what I was counting on the train?" he asked.

“Yes," I said.

"I was counting days," said Uncle Elephant.

"The days we spent together?" I asked.

"Yes," said Uncle Elephant.

"They were wonderful days. They all passed too fast."

This exchange between elephants, more so than any interview with their human creator, offered a telling window onto Lobel’s experience of fatherhood. Uncle Elephant’s counting of the days gestures at our adult sense of childhood’s brevity, its finitude. It also reminds me of how parenthood casts our mortality into sharp relief: we live with the sad awareness—but also the fervent all-consuming hope—that we’ll leave our children without knowing fully how their stories will unfold.

I also glimpsed a dad-like sensibility in the empathetic acts of caregiving that Uncle Elephant practices throughout the book. For instance, in the chapter “Uncle Elephant Wears His Clothes,” Uncle Elephant notices that his nephew is having a particularly hard day grieving his parents. So, he gamely makes himself ridiculous by wearing all the clothes in his closet at once, until his nephew cracks a smile. The act is at once goofy and tender.

Arnold Lobel, a year before his death.

Jesse Green uses this language of tenderness to describe the subversive ‘queerness’ of mid-century children’s books:

The tenderness of fathers has been on my mind since watching 2018’s Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, a documentary about the children’s TV host Mr. Rogers. Fred Rogers, too, was a lonely, outcast, sickly kid who carried that keen memory of childhood’s dark, lonely corners into adulthood. He made it his mission (and, as Carvell Wallace argues on the Finding Fred podcast, his ministry) to take children’s inner worlds and experiences seriously.

Rogers was straight, an ordained minister and dad of two. But, through his patient presence onscreen, Mr. Rogers, too, offered a wildly different—almost radical in its way—counter-narrative of how a man could be in the world. How his strength could derive from humility and receptiveness to others.

Lobel’s Frog and Toad are both flawed—at times needy, possessive, grumpy, despairing. (OK, these adjectives mostly describe Toad.) But whether consoling each other when sick or raking each other’s leaves, these two gay amphibians taught young readers about how to be loving adults, engaged in reciprocal acts of caring for one’s neighbor.

V.

I wrote earlier that the best children’s literature does not indoctrinate young people in how they ‘ought to be in the world.’ Well, the inverse is also true: the best children’s literature imagines the world as it should be. It animates our narrow reality with childhood’s magical sense of possibility, its urgent idealism.

Arnold Lobel, the father in the closet, helped to dream into being a more open, inclusive world. His works became “blueprints for blowing up the closet.” They also modeled a more nurturing, compassionate vision of masculinity.

Of course, in praising the quiet power of Lobel’s books, I don’t mean to ignore his decades of private sadness, nor his premature death in 1987, a casualty of the AIDS crisis. Lobel’s creative muse, and his envelope-pushing early readers, came at a great personal cost.

I do, however, want to celebrate his message. I want to trumpet it loudly and exuberantly, much as Uncle Elephant and his grand-nephew come together one morning to “trumpet the dawn”:

“We were the king and the prince. We were trumpeting the dawn.” From Arnold Lobel’s Uncle Elephant (1981).

NOTES

*Scholars of children’s books and young-adult fiction, of course, have been clamoring for such recognition for decades!

**I’m also reminded here of Robert Louis Stevenson, another writer and poet who had a formative childhood illness that might have led to his adult sense of kinship with children and young adults.

***Lobel’s daughter would later discover her father’s poems and black-and-white drawings featuring frogs and toads dating back to the 1960s, so Lobel was already working with these ideas. But they were bound as pamphlets and given as gifts to friends; they didn’t come to life, nor did they emerge from the literal closet, during that decade. The poems were instead published posthumously, with line art colored by Adrianne, in 2009.