When I was about 14-weeks pregnant, my ob-gyn called with the results of the genetic screening. After two weeks of suspense, a nurse was calmly informing me of my unborn baby’s fate while I waited at the bus stop.

As my heart pounded in my ears, the nurse delivered the news. In a call that lasted all of two minutes, she reported that the test results had come back negative for chromosomal abnormalities. She added, tapping distractedly on the computer, “Oh, and you’re having…um, let’s see here…a boy.”

The call ended; the bus arrived. Immediately after boarding, I broke down into messy public tears. I was shaken by the intrusion of such intimate details into the routine of my commute home. I felt overwhelmed with relief, but also, surprisingly, mournful about the news of the baby’s sex. Phoning my mom, I sobbed about my fears that my son would grow up to lose touch with me, to reject our early closeness.

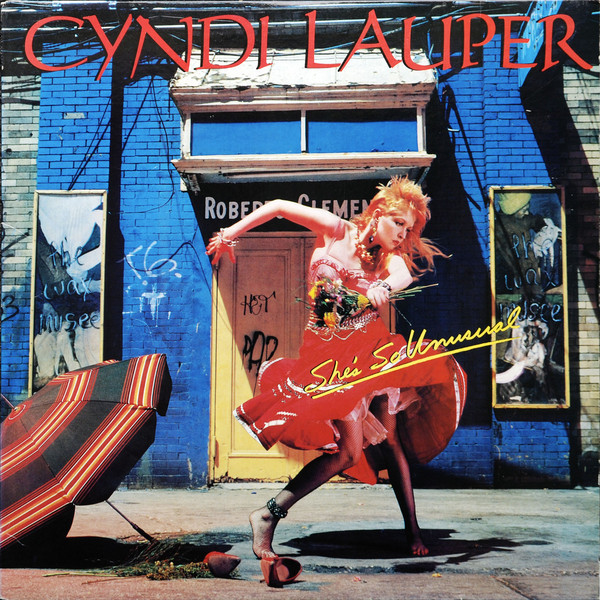

The following night, I was home alone doing dishes when the 1980s pop song “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” came on my playlist. This Cyndi Lauper classic is possibly the most cheerful, uplifting, positive anthem in the history of pop music. I burst into tears again.

I worried that my son and I would be missing some crucial connection, that we wouldn’t be able to ‘get’ each other, because of walking around in differently sexed and gendered bodies. I worried that we would never dance around together to “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun,” a favorite of my childhood (we have since danced around together to that song).

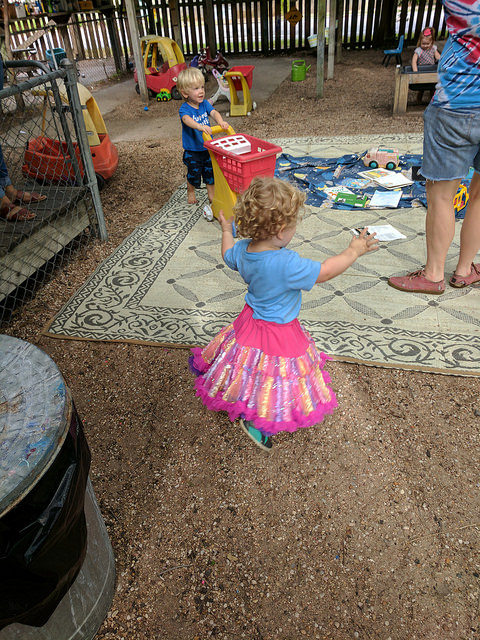

Images: the cover of Cyndi Lauper's debut album; my son at age 2.

All of my Gender 101 understanding vanished in the face of those test results. How much of who my child would become, and who he would know himself to be, did I really think I could discern from an XY chromosome? The “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” Incident highlighted to me how deep the roots of my gender socialization were, as well as the narrowness of such thinking.*

I was ashamed of my assumptions, and quickly promised myself that I would be on guard against them while raising my kid. But I know that’s naïve, that there will be tests. They’ve already begun. They began instantly, with the gendered infant clothes (E.g., ‘Do I not put my baby in the blue “Daddy’s Little Slugger” onesie when it’s free, on loan from a friend, and baby clothes are so expensive?’).

Navigating gender with my child will get harder in the years ahead. I wonder, though, if he will be less my student than my intrepid, enlightened guide on that journey. Already, he’s exposed some of my biases, challenged me to think about gender in new ways. Already, he’s been teaching me.

Ever since I caught a glimpse of Lynn Conway’s bio, just a sentence or two about her while researching my Ada Lovelace book, I couldn’t shake her story.

At the same time, I had reservations about sharing her biography on this blog. I tend to traffic in figures dead and buried. Riffing on a living person’s creative life and parenting experiences – Conway is now eighty – is a little more, well, personal.

But mainly, as a cisgender woman, I worried about appropriating Conway’s story, especially since Conway herself has written extensive hyper-linked memoirs chronicling her experiences.

That said, the more I looked, the more I saw that Conway’s life spoke to so many topics that are central to this space and close to my heart, from handling the ruptures in our lives to exploring the creativity that underlies science and engineering.

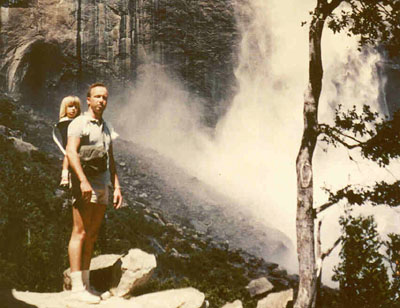

There is another factor, though, that makes her story difficult to tell. Despite its hopeful, freeing aspects, at the center of Conway’s male-to-female transition in 1968 was loss. To find herself, or, rather, to live in a way that was true to herself, Conway had to let go of her past. A past that included two young children.

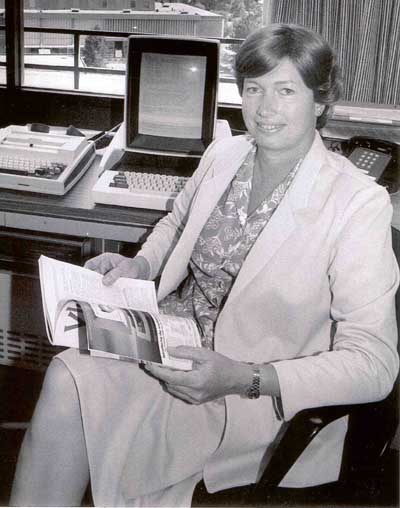

In the 1970s, Conway pioneered what has become known as the “VLSI revolution” while working at the famed Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) – the process of fitting ever more, and even more compact, transistors on integrated circuits – lies behind the emergence of everything from personal computers to smartphones.

Along with Carver Mead at Cal Tech, Conway literally wrote the textbook on microprocessor design. Introduction to VLSI Systems would influence a generation of chip designers.

What’s striking is the sense of freewheeling play and creativity that animated her work at this time. Conway uses an analogy to art history to describe her approach to inventing a new way to design microchips, which had previously been the exclusive domain of big semiconductor firms like Intel:

I could envision that it could be like opening up Impressionism…. All kinds of people who could never paint well in the old way could then figure out how to do something new, impressionistically. And they could say things none of the other people knew how to say.

The sheer pleasure and freedom Conway expresses in these lines makes it hard to imagine that, a decade earlier, she had nearly ended her life.

Images: Hiking with daughter, 1966. Post-transition, working at PARC in 1983.

At the time, Conway was living, unhappily, as Robert. It was Robert’s spouse Sue who talked him down from suicide. They agreed to divorce, but their amicable separation faltered due to social pressures and stigmatization, particularly after Conway was fired from IBM after coming out as transgender. Still required to pay child support, Conway was denied any contact with her two daughters, aged 4 and 2 at the time.** Recalling the separation decades later, Conway reflected,

“That tore me up, let me tell you…It’s long enough ago now that I don’t get choked up, but the hardest part about the whole thing was that. I felt like a mom to them.”

For someone whose work involved integration, integrated circuits, Conway’s life seems to divide into stark befores and afters. After her early professional success at IBM, she was tasked with rebuilding her career from the ground up. After a conventional life with two children, she was suddenly living on her own as a woman. She felt like she was in the witness-protection program, like “an undocumented alien from Mars.”

Nonetheless, we can also approach Conway’s story in ways that emphasize the continuities, starting with the long-awaited integration of her sex, gender identity, and gender expression when she transitioned to female in the late 1960s.

There’s also the belated integration of the two halves of her professional life, after a computer historian made the connection in 1999. Not only did this lead to a new appreciation of her achievements in the industry, it also sparked Conway’s trans activism. Despite her quiet, introverted nature, the decades she had lived in what she termed “stealth mode,” Conway decided to publicly share her story in order to give hope to others.

As you can see from her memoirs, the stories of her transgender experience and her work at the vanguard of the microprocessing revolution are intimately entwined.

Conway was pioneering not just as a computer engineer but as a trans woman. She was one of the first transsexual women to undergo sex-reassignment surgery.

Above all, creativity is such a crucial through-line in Conway’s life. Her ‘gender trouble’ demanded and strengthened her flexibility and resourcefulness as a scientist. She explains:

In important ways, I approached my personal gender explorations like yet another area of my work as an innovative research engineer - for here too I was pathbreaking, trying to find my way in a maze of complexity and dissonance, trying to use science and innovative experimentation to solve a very fundamental problem.

Key to her adaptability, her resilience in both starting over as a woman and starting over in her tech career, was her embrace of the creative potential of beginning again:

“A lot of it has to do with learning how to do new things – how to not be afraid to be a beginner, to just be kind of a quiet child and just observe,” she says. “And then, it’s kind of like, ‘Why not question everything?'"

I’m inspired by Conway’s bravery in beginnings. Although becoming a parent is a less dramatic reinvention of the self than Conway’s experience of gender transition, it is a transformation nonetheless. Rather than bemoaning a lost self, can we harness our newbie bewilderment and disorientation for good? Conway’s example suggests that our creative lives will benefit from acknowledging our status as novices, from having to rediscover ourselves both personally and professionally. And, forced to see ourselves and the world anew, we might also learn to “question everything,” beginning with the burdens of gender norms.

NOTES

*What's especially strange about this is that Cyndi Lauper represented to me, even though I couldn't articulate it as a kid, a freedom of gender expression (embodied even in the title of her debut album) that I didn't get from other singers of the time like Debbie Gibson. As Sheila Moeschen puts it, "the young girl from Queens, embodied a different kind of feminine aesthetic .... [Lauper] introduced a nation of women to a new kind of female role model, one that celebrated difference and encouraged playfulness in self-expression."

**There is, however, a happy ending to this story! When her daughters turned 18, they reconnected with Lynn first through letters, then visits. Conway boasts, “I'm probably closer now to Robert's children (as their Aunt Lynn) than most parents are with their adult children.”