My almost-three-year old has been embarking on brief, intense friendships with books these days. One endearing example: he’ll sit on a picnic blanket munching on a jam sandwich while conversing freely with the badger Frances of Bread and Jam for Frances.

Another recent infatuation involved a copy of a Little Golden book from my own childhood: A Child’s Garden of Verses by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. In 1957, Eloise Wilkin illustrated and edited the abridged Little Golden Books version of A Child’s Garden of Verses, originally published as Penny Whistles in 1885. Although Wilkin’s drawings of cherubic white kids and suburban spaces are very 1950s Americana, the poems retain a certain wild freedom and exuberance and fun.

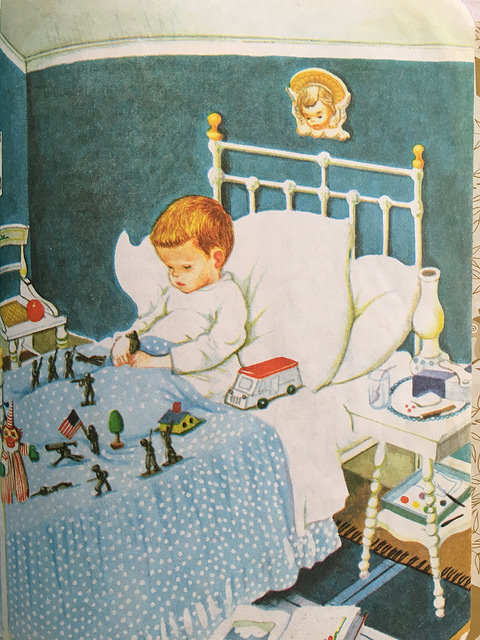

My personal favorites as a child included “My Shadow,” “Bed in Summer,” and “The Swing.” But my toddler was particularly taken with Stevenson’s poem “The Land of Counterpane.” The accompanying illustration depicts a young boy asleep in his sickbed, with an array of playthings – from toy soldiers to tiny houses and trees – keeping him company on the quilt. (RSL took inspiration from his own sickly childhood for this poem; he even dedicated the collection as a whole to his childhood nurse.)

One morning my son asked to set up a facsimile Land of Counterpane on our bedspread, with his toys strewn about the covers (see photo).

“I was the giant great and still / That sits upon the pillow-hill”: play inspired by the RSL poem "The Land of Counterpane."

For no other reason than that my son dug this poetry collection and that I remember being captivated by it as well, I decided to dabble in some Robert Louis Stevenson research.

There are a lot of promising angles onto the Scotsman’s short life and prolific career. His late-life travels in the Pacific. The longevity and continued resonance of his books for children (my mother-in-law had a copy of A Child's Garden of Verses on her shelf). The constant backdrop of illness that would shadow Louis (reviewing one of his books, Rudyard Kipling quipped, “That man has only one lung but he makes you laugh with all your whole inside”). The vagaries of his literary reputation: dismissed in the early 20th century as a mere children’s author of swashbuckling adventure tales, and recently reconsidered.

Louis (seated, center) with his family in Samoa. The lanky, bespectacled young man at left is Louis's stepson Lloyd.

But what really captivated me, and felt most relevant to this blog about parenting and creativity, was a passage from Stevenson’s Essays in the Art of Writing. In it, he offers an origin story for one of his most famous books, Treasure Island. He recalls a habit of drawing alongside his 12-year-old stepson Lloyd (Sam). He had married Lloyd’s mother, the American Fanny Osbourne, the year before. The pair had met years earlier in France, where Fanny was on an artist’s retreat while separated from her first husband.

Stevenson had warmed to the then-seven-year-old immediately, and the feeling was reciprocal. Lloyd would fondly remember Louis’s reappearance in Monterey, California, where Louis had journeyed to plead his case with Fanny: “I remember him walking into the room and the outcry of delight that greeted him, the incoherence of laughter, the tears, the heart-swelling joy of reunion.”

According to biographer Eileen Dunlop, “[Louis] loved the company of children and clearly was sometimes saddened by the lack of his own.” RSL developed a close relationship with Lloyd, eighteen years his junior. He recalls that he would:

...join the artist (so to speak) at the easel, and pass the afternoon with him in a generous emulation, making coloured drawings. On one of these occasions, I made the map of an island; it was elaborately and (I thought) beautifully coloured; the shape of it took my fancy beyond expression; it contained harbours that pleased me like sonnets; and with the unconsciousness of the predestined, I ticketed my performance Treasure Island…. As I pored upon my map of Treasure Island, the future characters of the book began to appear there visibly among imaginary woods….The next thing I knew, I had some paper before me, and was writing out a list of chapters.

In adulthood, Lloyd, himself a writer, would go on to co-author three books with his stepfather, before RSL’s untimely death at age 44.

There’s something especially sweet and unexpected, though, about that early, more spontaneous collaboration.

That particular image of Louis and Lloyd at their easels got me thinking about play. Despite doing so much play with my young son, it’s often not the kind of play that I’d choose to do on my own. I participate gamely, but I’m often bored by the repetition of toddler games. Play, in short, can feel like work.

Occasionally, though, there are moments, like that exchange between Louis and Lloyd, when our play dovetails and feels mutually enriching. When we are both truly at play.

The Treasure Island anecdote reminded me of an experience from a few months ago when my son and I collaborated on a book of our own.

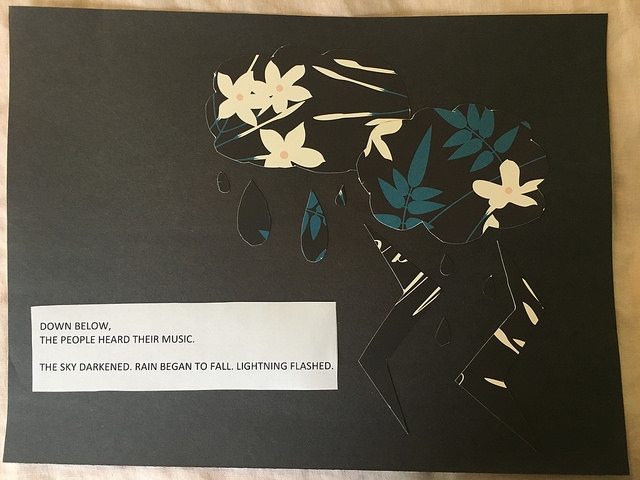

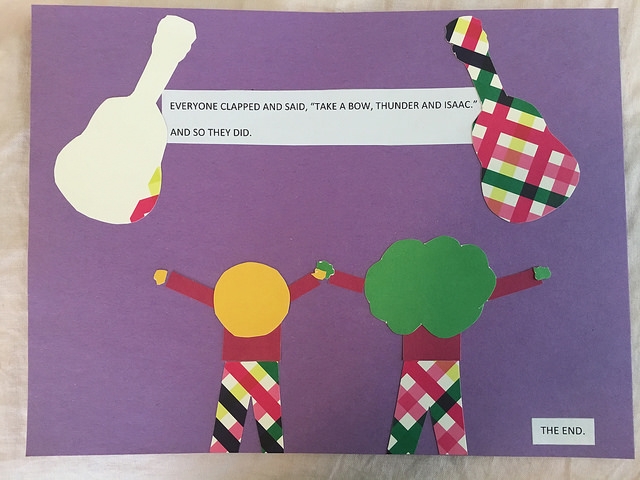

Our partnership began on a road trip last summer, when my then 26-month-old son started making up this wild tale about thunder. He was in that manic state that comes just before a deep crash into sleep. He invented a story that had him traveling up to Thunder’s house in the sky to wake him up with a violin. Thunder was a little kid like him with an impressive array of musical instruments. His music was heard down below as a cacophony of sound and storm.

My son had been petrified of his first real thunderstorm earlier that summer. His body just froze, got really still, as the Central Texas storm raged. So, I was amazed at how this inventive story helped him process his fears. By linking the frightening thunder with his love of music, he transformed the thunderstorm into a friendly bandmate.

A few months later, I was feeling stuck while writing a first draft of my Ada Lovelace book. The novelty of writing the manuscript had worn off, and I felt lonely and uninspired.

At that moment, I experienced a strong urge to make a physical book out of my son’s story. A keepsake and procrastination device all in one.

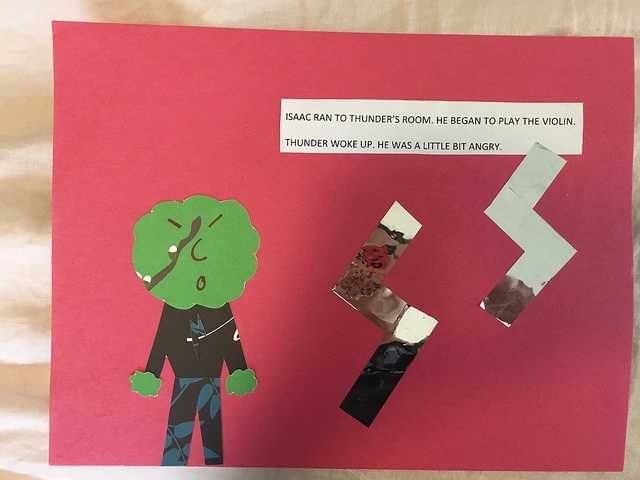

I spent several hours of the next two ‘work days’ making meticulous paper cut-outs to accompany the simple text (see photo).

A few pages from a children's book collaboration with my son.

In the end, my son liked the book fine. He didn’t really have a sense of the time I’d put into this handmade, imperfect artifact. For me, though, the process of creating the book was profound. It cleared the cobwebs or burned off some restless energy or generated some positive mojo or something. All I know is that after those couple of days’ hiatus, I was ready to work on my book manuscript again.

The takeaway is not that I stumbled upon my true vocation as a children’s book author. One doesn’t have to write about/for children to find fuel for one’s creativity in parenting. There are more subtle forms of creative influence between parent and child.

In our case – and in the case of Louis and Lloyd and that famous adventure tale – collaboration took the form of a parent (or step-parent) accepting an invitation to play.