“To all the moms out there, I was playing out there for you today, and I tried.”

- Serena Williams, after her 2018 Wimbledon loss

I’m training for my first half-marathon. At age 39. This would not be remarkable, except that I’ve spent most of the previous 38 years convinced that I am genetically ill-equipped for any form of athleticism. Historically, I’ve also been virulently opposed to following sports as a spectator (aside from a couple of years in college when I was dating a cute baseball player and transformed briefly into an ersatz Mets fan).

Somehow, though, here I am. Running!

A guilty pleasure these days on my distance runs is to listen to the Nike Run Club podcast. My inner Gen-X teenager rolls her eyes so hard at the corny, cliché-ridden scripts.

But the clichés do the trick. Coach Bennett’s motivational speeches about “becoming a better you” on the Run That is Life keep me moving. When my middle-aged body is at its creakiest and most vulnerable, I’m a sucker for a Nike slogan.

And as I embark on this two-part post, about athletes who are, or were, also mothers, perhaps some triteness is inevitable.

Without resorting to the pat or familiar, how do we articulate the ways that physical activity can spill over into our mental and emotional states? How a body in motion can set our creativity in motion? How it can relax or rejuvenate us, even unlock, at unexpected moments, intense feelings of gratitude or grief?

Be forewarned, then: by the end of this essay, I’ll probably be telling you to “Just do it.”

Joan Benoit, Runner

This post was inspired, in part, by a mother-daughter conversation I listened to recently on Nike Run Club. The mother, by the way, was legendary long-distance runner Joan Benoit Samuelson. In 1979, the year of my birth, she won the Boston Marathon. (This was only a handful of years after Kathrine Switzer’s efforts had opened up the marathon to women.)

In 1984, Benoit won the Gold medal in the first ever women’s Olympic marathon, held in Los Angeles. Soon after, she retired from the sport to raise a family. She jokingly divides her life into two eras, B.C. and A.D., for “Before Children” and “After Diapers.” She gave birth to daughter Abby in 1987, and son Anders two years later.

When Abby asked her mother what it felt like to leave the sport at the height of her powers, Benoit expressed no ambivalence about her choice. At least for the purpose of the guided run I was listening to (and I suspect the truth is more complicated), Benoit insisted she had no regrets, that her children were her most important achievement.

As we’ll see, not all mother-athletes’ careers follow that tidy B.C. / A.D. timeline.

Joan Benoit, after her 1984 Gold medal victory in Los Angeles.

In the podcast, Benoit described the motivating power of storytelling. Stories had fueled her return to running marathons. Like how, at age 50, she wanted to run in the 2 hour and 50-minute range, a neat symmetry. So, in 2008, she ran in the U.S. Olympic Team trials, finishing in just over 2 hours and 49 minutes and setting a new U.S. record for runners 50 and over.

Benoit’s comment got me thinking, though, about the dark side of storytelling. How stories can be empowering but also limiting, if not downright false. Homo sapiens might be “the storytelling animal,” but our stories can sometimes lead us astray, down dangerous paths of inadequacy and self-doubt.

My own internal narratives, about both writing and running, are predominantly about failure. I inwardly resist identifying as a “writer” or as someone “creative.” I roll my eyes whenever Coach Bennett refers to me as an “athlete” on the Nike app.

What would happen if, instead, I let go of some of those burdensome plot lines? I picture a sudden burst of lightness and speed…an imagination powered by Usain Bolt.

Serena Williams, Tennis Legend

My other inspiration is, of course, tennis icon and new mother Serena Williams. I hesitate to write about Williams, sports, and motherhood, because so much ink has already been spilled on the subject. Williams, however, must be talked about. She has, after all, set the terms of a modern conversation about mothers in professional sports.

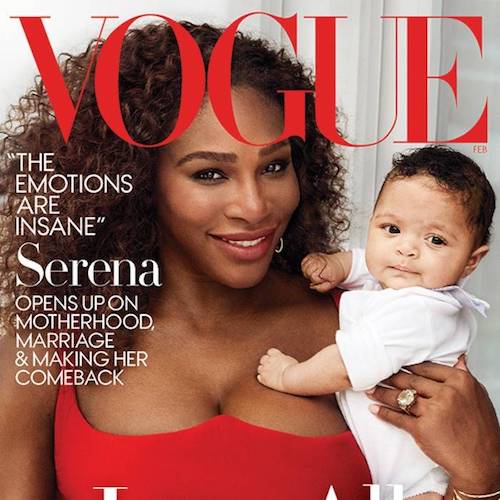

Since announcing her pregnancy in early 2017, and giving birth to daughter Alexis Olympia in September of that year, the 37-year-old Williams has made motherhood a crucial part of her identity as an athlete. She has used her platform to become a vocal advocate for working mothers.

Images: Williams on the cover of Vogue (left) and competing at Wimbledon in 2018 (right).

Williams has initiated this important conversation, or really a set of important conversations, not just about mothers in sport, but about working motherhood more generally. She has also spoken out about the invisibility of black mothers in the healthcare system, using her own childbirth scare, which began with a pulmonary embolism after giving birth, as a call to awareness and action.

Williams’ public performance of motherhood has resonated so powerfully because we can see our everyday challenges as mothers mirrored in the experiences of an extraordinary athlete. She struggles with breast-milk supply in the documentary “Becoming Serena.” She posts infatuated love-letters to baby (and now toddler) Alexis Olympia on Instagram and Twitter. Louisa Thomas writes,

At the same time, Williams aspires not just to continue participating in her sport, but to continue dominating it. As she admitted in a Vogue interview early last year, full-time motherhood tempts her, but the pull of achieving a 25 Gram-Slam world record is stronger:

“To be honest, there’s something really attractive about the idea of moving to San Francisco and just being a mom. But not yet. Maybe this goes without saying, but it needs to be said in a powerful way: I absolutely want more Grand Slams… And actually, I think having a baby might help. When I’m too anxious I lose matches, and I feel like a lot of that anxiety disappeared when Olympia was born. Knowing I’ve got this beautiful baby to go home to makes me feel like I don’t have to play another match. I don’t need the money or the titles or the prestige. I want them, but I don’t need them. That’s a different feeling for me.”

Williams has explicitly framed her return to tennis as a public, real-time memoir of her working motherhood. If the results so far have been mixed, that is no matter: the force of her appeal is in the very visible nature of her striving.

But Williams is by no means the only female athlete, past or present, to grapple with motherhood’s demands on the body and mind. Below, a brief, idiosyncratic survey of athletes and adventurers from history whose stories have given me a new sense of lightness and speed.

Annie Londonderry, Cyclist

If you haven’t read up on the intertwined history of women’s suffrage and bicycling, you should do so immediately.

Then, come back here to learn about a Latvian immigrant to the U.S., and mother of three, who circumnavigated the globe. On a bike. In 1894.

…

The story goes that two anonymous Boston businessmen had made a bet, $20,000 to $10,000, that a woman couldn’t match the globe-trotting achievement of a man, Thomas Stevens, who had ridden 13,500 miles by bike a decade before. The conditions of the wager: she would have only 15 months to complete her journey, and would have to depart without any cash, surviving on her wits and earning $5,000 above her travel expenses.

Annie Kopchovsky (born Anna Cohen) seemed an odd choice to take up this challenge. Aside from a couple of quick lessons two days prior to her journey, she had never ridden a bicycle.

She was also the 24-year-old mother of three young children, aged 5, 3, and 2. Even in 2018, such a long absence from one’s family might give some naysayers pause; in 1894, it was downright scandalous.

Moreover, Kopchovsky, an Orthodox Jew, faced the blatant anti-Semitism of the time.

On the other hand, the choice made perfect sense…because that wager was utter B.S.

Kopchovsky probably invented the story herself. Her motives are lost to the historical record, but likely involved some combination of wanting to earn money through ad revenue, achieve global fame, and strike out for adventure outside of the domestic claustrophobia of family life. Prior to the trip, she sold advertising space for several daily Boston newspapers, and she had a natural flair for self-invention, theatrics, and outright lies.

Here is a smattering of the tall tales she told when interviewed along the bike route: that she was an orphan who’d inherited enormous wealth; that she held a law doctorate; that she was planning to finish her studies at Harvard Medical School after the trip was over.* For the New York World, she detailed her (fictitious) imprisonment in a Chinese jail cell during the Sino-Japanese war. Somewhere outside of San Francisco, she staged a photo of herself being held up by highway robbers in the French countryside!

Images: Londonderry posing with her bike in 1894. A cartoon depicting fears that women’s newfound independence on the bike would leave fathers stranded at home with caregiving duties.

The public, and the sensationalistic newspapers of the day, ate it all up. One French publication observed that “(Londonderry) seems made only of muscles and nerves and in spite of her petite size gives the impression of remarkable energy.” “She has a degree of self-assurance somewhat unusual to her sex,” opined a writer for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Kopchovsky’s taste for embellishment, and, to be frank, her middling abilities as a cyclist, don’t negate the stunning audacity of her journey. As Peter Zheutlin, a great-grandnephew of Annie’s who came to research her story, put it:

So, Kopchovsky found sponsors. She rode with commercial endorsements, for everything from milk to perfume, blanketing her bike and person. One, in particular, from Londonderry Lithia Spring Water company of New Hampshire, gave birth to her new cyclist persona: “Annie Londonberry.” It had the dual function of helping to pay her way and disguising her Jewish surname.

Her combination of stamina, moxie, and savvy branding also foreshadow the demands on the modern athlete, asked to be a hybrid of sports-person, self-promoter, and entrepreneur.

Kopchovsky’s only possessions, as she set off from Boston’s State House in June 1894, were an extra pair of underwear and a pearl-handled revolver. About four months into the trip, she acquired a pair of bloomers and a new (men’s) bike, which was a whopping 20 pounds lighter than the women’s models available at the time.

Kopchovsky made her way by steamship from the Eastern U.S. to France, and onward to parts of the Middle East and Asia, before returning to the West Coast. She arrived in Boston 15 months to the day of her departure, triumphant save for a cast acquired in rural Iowa after an unfortunate collision with a drove of pigs resulted in a broken wrist.

Fanfare ensued. The New York World declared Kopchovsky’s cycling trip “the most extraordinary journey ever undertaken by a woman.”

After the record-breaking feat, however, Kopchovsky mostly faded into obscurity. She moved her family from Boston to the Bronx, had a fourth child. But before she disappeared entirely from the public stage, she embarked on a brief career writing sensational features for the New York World, under the provocative and oh-so-au-courant byline “The New Woman.”

According to Zheutlin, Kopchovsky was a nominal feminist, or at best a “feminist of convenience.” Riding feminism’s first wave, which saw the bicycle as a tool of women’s social and political liberation, Kopchovsky peddled her way into international renown. But whatever her personal motives for undertaking the journey, she advanced that larger cause with every muddy backroad she pedaled, with every fabulist’s story she fed to an adoring public.

Georgia “Tiny” Broadwick, Parachutist

Maybe I have a soft spot for Tiny Broadwick because of her size: barely 5 feet tall, around 85 pounds. We petite ladies are often teased about our height, discounted, overlooked (literally), which only gives us something extra to prove.

Everything about Tiny’s backstory predicted that she would be counted out. Born in 1893 into a poor farming family in Granville County, North Carolina, she weighed only 3 pounds at birth. Tiny married at age 12, became a mother at 13, and was abandoned by her husband soon after.** As a teenaged single mother, she worked 14-hour days in a cotton mill to support her daughter Verla.

Then, came the possibility of escape. It appeared in the form of Charles Broadwick’s traveling aeronautics show, which landed in Tiny’s part of the world in 1907. She was instantly captivated by the performers leaping from hot-air balloons with parachutes. She approached Broadwick after the show and convinced him to hire her to do the same stunts. Broadwick capitalized on her youth and diminutive size by billing her as “the doll girl,” a moniker that she reluctantly assumed.

Traveling with Broadwick’s troupe, however, meant leaving Verla behind to be raised by her grandmother. Although Tiny had regrets, she felt that Verla’s upbringing was better than what she could have provided: “I’ve talked to God many times about the care my mother took of my daughter.”

By the early 1910s, Tiny had traded out hot-air balloons for airplanes. Teaming up with aviator Glenn Martin, she became the first woman to parachute from a plane (floating into Los Angeles’s Griffith Park). She was also the first woman to parachute into a body of water (Lake Michigan). And the first person of any gender to make a planned free-fall descent.***

Tiny Broadwick posed beside a plane in flying gear, with parachute, circa 1912. Via the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Due to chronic ankle troubles, Tiny retired at age 29. By that point, though, she had made over 1,000 jumps.

Tiny’s pioneering exploits in the air did not offer a permanent escape from her working-class roots. She would later work on an assembly line in a tire factory, become a caregiver for the elderly.

But in that earlier time, faced with the tough choice between a grueling routine with Verla and the enticement of the skies without her, Tiny chose adventure. A chance, in a sense, to put motherhood on hold and reclaim her own lost childhood.

There’s this great interview with Tiny from 1963, when she was 70 years old. The male interviewer, looming over a foot taller than her, speculates on how frightening that first parachute jump, back at age 15, must have been for her. Tiny pauses, then says simply:

“It never bothered me.”

Tiny Broadwick, circa 1913.

…

Training for distance runs has taught me that running is partly, maybe even predominantly, a head game. But while the link between mind and body is undeniable, I felt moved to write about mother-athletes because the topic calls particular attention to our bodies.

Of course, whole libraries could be filled on the subject of women’s bodies and how culture has done them wrong. But I want to talk specifically here about female bodies in relation to pregnancy, fertility, and childbirth. How they are, as in so many other areas of life, medicalized, pathologized, shamed, dismissed, viewed as inadequate or weak or wanting.

The twice-daily hormone injections of IVF treatments. The vaginal tearing that infuses those postpartum trips to the bathroom with an aura of dread. The struggle of healing from a C-section (aka major abdominal surgery) while home with a newborn. The referred pain, plugged ducts, yeast infections, and other small traumas of the so-called ‘natural’ act of breastfeeding. (And this is bracketing all of the head stuff – postpartum depression, suddenly welcoming a four-year-old into your home as an adoptive parent, etc., etc.)

Rarely are pregnancy, fertility treatments, the postpartum period, or fostering/adoption framed as tests of mental and physical stamina, akin to athletic training. Rarely do we celebrate the strength required to make and/or raise new humans. (Beyonce is a noteworthy exception: “Strong enough to bear the children / Then get back to business.”)

My body while I run is both beautiful and broken. By mile 4, my lumbar region starts to call attention to itself, to complain, my back problems a legacy of a very petite woman carrying around a very hefty baby, now a kid, for the past 3.5 years. By mile 8, I might have peed a little, an embarrassing side effect of my vaginal delivery.****

What, exactly, is beautiful, then?! The fact that I’m running at all. The fact that I’m still here on this route, in this race. My newfound indifference to how this body appears to others I pass along the way.

I might be a short-limbed, red-faced, graceless athlete, but Coach is right: I am an athlete nonetheless.

P.S. Thanks, reader, for sticking around to the end of this post, which turned into an endurance test in its own right! Stay tuned for Part Three, on Olympic runners Fanny Blankers-Koen and Wilma Rudolph.

NOTES

* For the most part, Londonderry gave the impression to journalists that she was a single woman. Whenever she admitted to having a family in interviews, she was quoted as saying, “I didn’t want to spend my life at home with a baby under my apron every year.”

**The facts of Tiny’s biography, like Tiny herself, are a bit difficult to pin down. Some sources have it that her husband died in an accident while they were still married. There are similar discrepancies about how Tiny, born Georgia Ann Thompson, acquired the last name Broadwick. While most accounts suggest that Charles Broadwick legally adopted her, at least one claims that they lived as a married couple.

***This discovery was made during World War I, when the U.S. Army had recruited Tiny to help them figure out how to save pilots’ lives when jumping from a falling military plane.

**** 2019 resolution: get that taken care of.